Our Rich History

Here we celebrate Flat racing’s rich history, dating back to the 17th century. Over 400 years in the making, hundreds of thousands of equine and human participants have contributed to the sport we see on racecourses across the globe today.

Over the course of the year, and prior to QIPCO British Champions Day, this section will be updated with a series of features and stories looking back through British Flat racing’s rich history, starting in the 1600s. Crafted by the likes of Racing Journalist, Mary Pitt and Racing Historian, Chris Pitt, here you will learn about some of the most seminal moments and influential figures from the 17th century onwards.

A Step Back In Time…

Horseracing in Britain can be traced back to Roman times. When Julius Caesar invaded in 55 BC, he brought charioteers who had honed their skills in competition. However, the 17th century was when the sport developed on a more organised basis, thanks largely to the Stuart dynasty, in particular the enthusiasm and support of King Charles II, the Merry Monarch.

1605

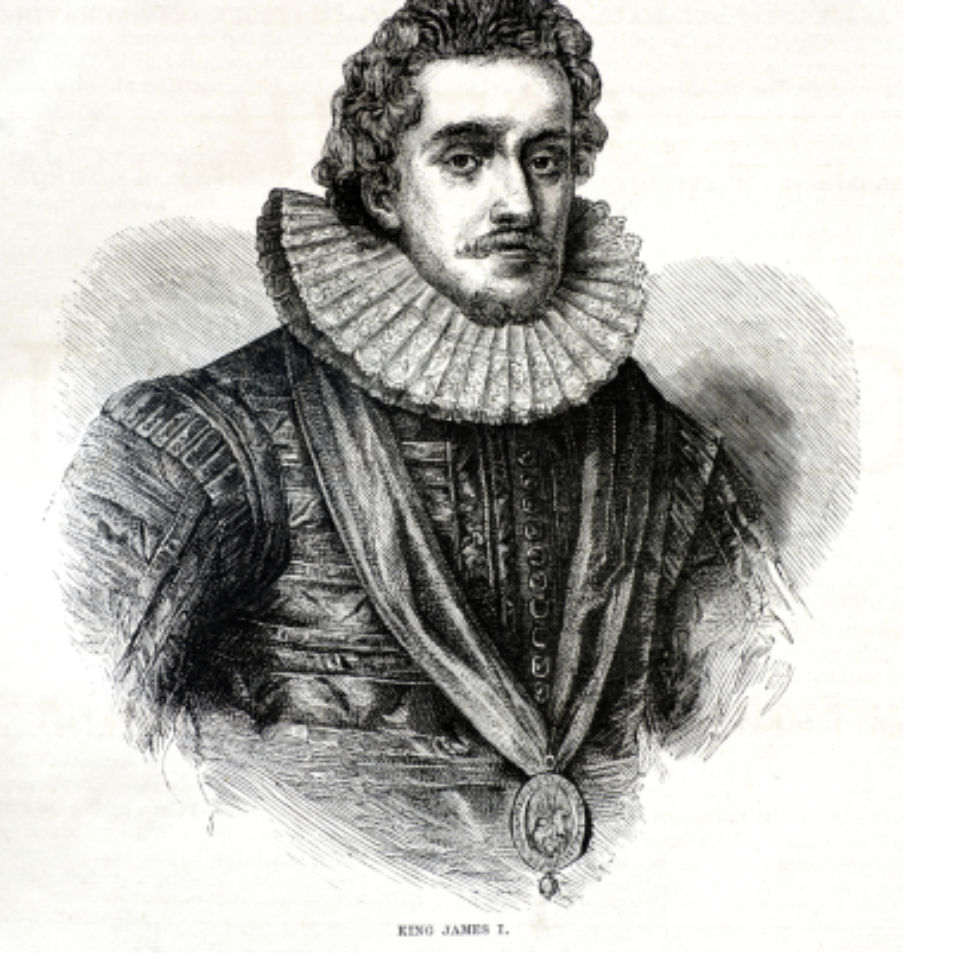

Long before Charles became king, James VI, the last king of Scotland, ascended to the English throne as James I in 1603, succeeding his mother’s first cousin, Queen Elizabeth I. His greatest contribution to the sport of horse racing – although it happened almost by accident – was to establish Newmarket as its headquarters.

Devoted to all forms of field sports, he first visited the area in 1605, two years after inheriting the throne, to hunt with his hounds and falcons, sometimes staying for weeks at a time. He developed a liking for the grassy plains of Newmarket Heath, lodging at a small inn called The Griffin in Newmarket itself. Eventually, finding The Griffin’s facilities a touch too primitive for his tastes, he built a palace on its site.

1609

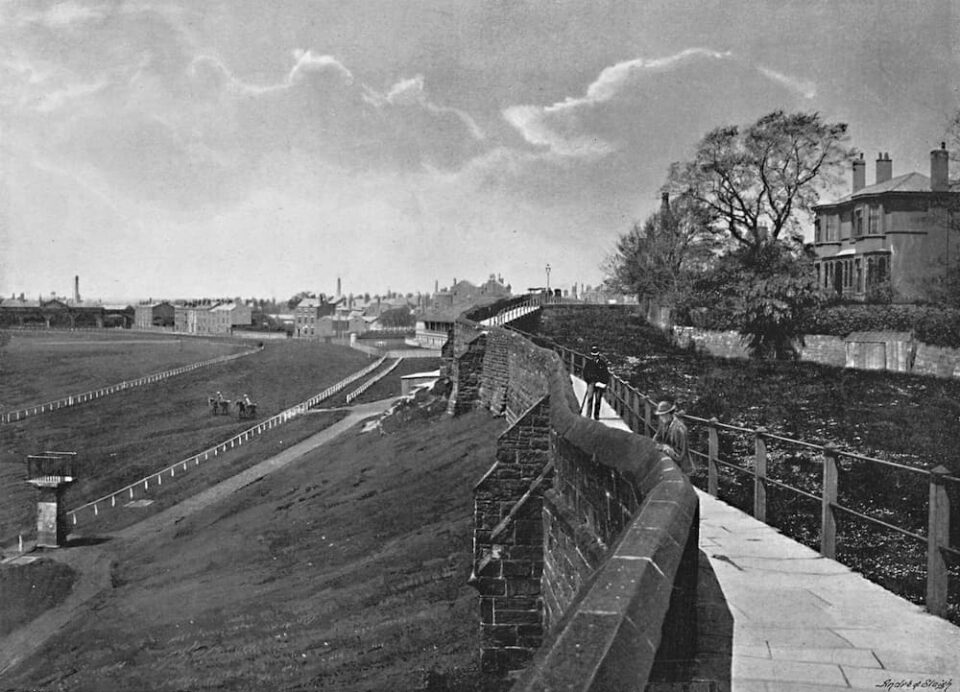

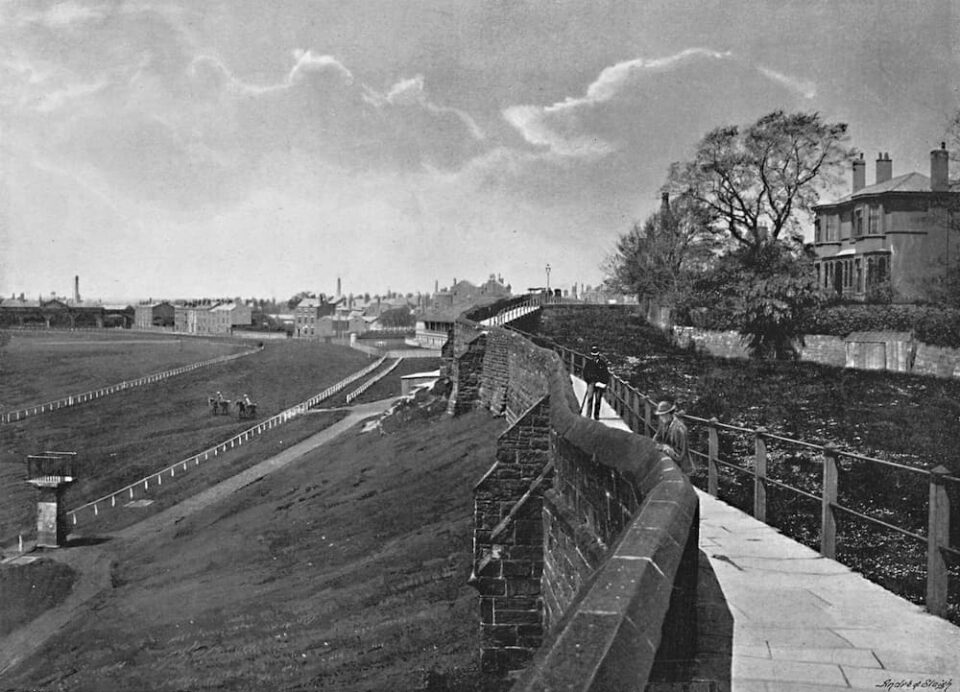

By then, horseracing was a growing sport around the country. Several courses that we know today were already staging meetings. Chester’s Roodee, overlooked by its Roman city wall, has legitimate claims to be the oldest. For many years it had held race meetings on Shrove Tuesday but in 1609 they were moved to St George’s Day, April 23, when the main event was for a prize of three bells, or cups … “being for the Kynge’s crowne and dignyte, and the homage of the Kynge and Prynce with that noble victor, St George, to be continued for ever”.

Bells were a common form of prize in those days. Henry Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, donated a golden bell worth £50 (equivalent to £12,770 today) for a three-mile race at Salisbury. Of those that survive today, the Lanark Silver Bell (run now at Hamilton since Lanark’s closure in 1977) is said to have been instituted by King William the Lion of Scotland. The Carlisle Bell bears the inscription ‘The Sweftes Horse Thes Bel To Tak For Mi Lade Daker Sake’. It is mentioned in the city records in 1619 when Carlisle’s race meetings were revived.

1614

Elsewhere, a map of Doncaster shows a racecourse at ‘Wheatley Moor’ upon which a grandstand had been erected by the dawn of the 17th century. By 1614 it had appointed a groundsman, who was paid one shilling and sixpence for “making the waye at the horse race”. However, his employment did not last long, for the following year the Corporation banned racing there “for the preventinge of sutes, quarrels, murders and bloodsheds”. It eventually resumed, albeit intermittently and was of only minor importance for the remainder of the century.

References to race meetings at Leicester appear in the Chamberlain’s Accounts throughout the 17th century, the earliest including a bill for “5s 8d (about 28 pence) to pay for one gallon of sack (wine) and one pound of sugar to the gentlemen at the horse-running”. Another records nine shillings and fourpence (about 47 pence) being disbursed “for a gallon of sack and two gallons of claret given to Sir Thomas Griffin, Sir Wm Faunt and other gentlemen, at the Angel, at the horse running”.

1634

During King James’s many visits to the races at Newmarket and elsewhere, he was often accompanied by his son Charles, Prince of Wales. When Charles inherited the throne on the death of his father in 1625, he too travelled far and wide to enjoy racing.

Charles I was a much better horseman than his father but arguably not quite as obsessed with horseracing, being far keener on hunting, but he regularly attended Newmarket’s Spring and Autumn meetings and maintained the royal studs. In 1634 he presented Newmarket with its first Gold Cup.

Following Charles I’s demise at the hands of Cromwell’s New Model Army in 1649, the republican government put a stop to horse racing, not least due to the sport’s Royalist image. The previous year, during the English Civil War, a group of Royalists met on Epsom Downs “under the pretence of a horse race … intending to cause a diversion on the King’s behalf”. Thus, racecourses were seen as potential venues for organising plots against the Great Rebellion.

1655

Even the Lord Protector himself, Oliver Cromwell, did not completely kill off the sport. Although his parliamentary soldiers destroyed the royal studs at Eltham and Tutbury, the Council of State acquired the Tutbury horses, declaring that they were the best in England and should not be dispensed. The hypocrisy was that Cromwell himself appreciated good horses, enough to import them from Italy and the Middle East.

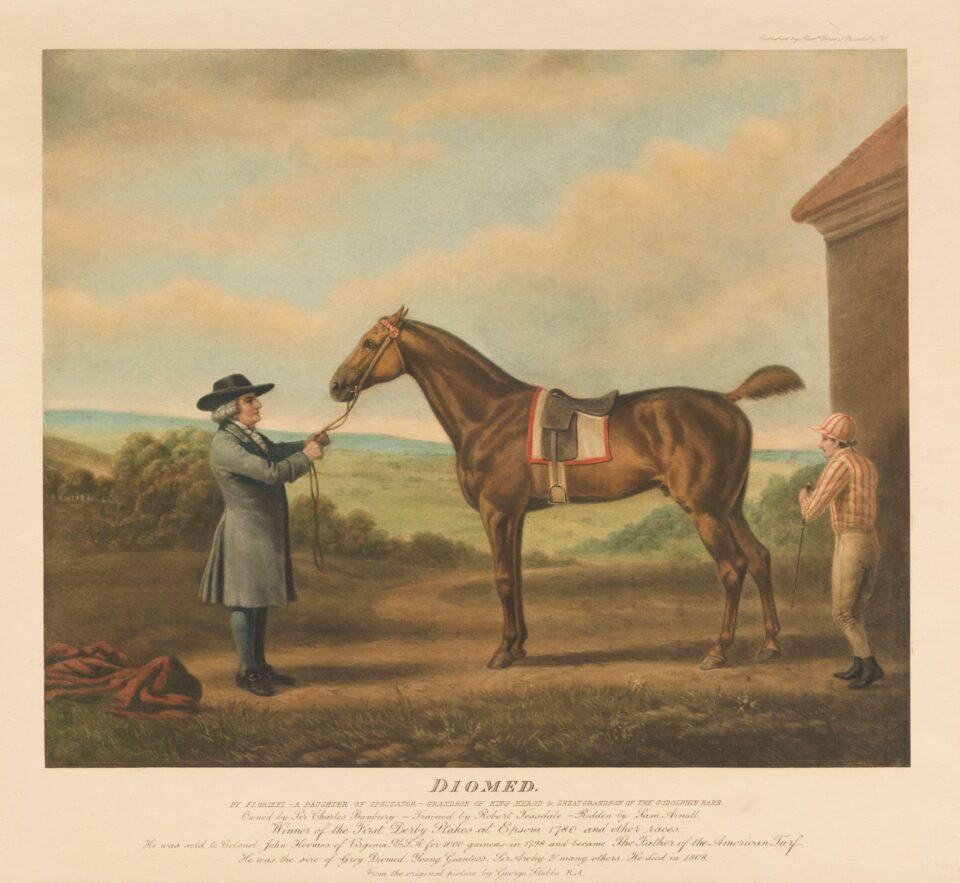

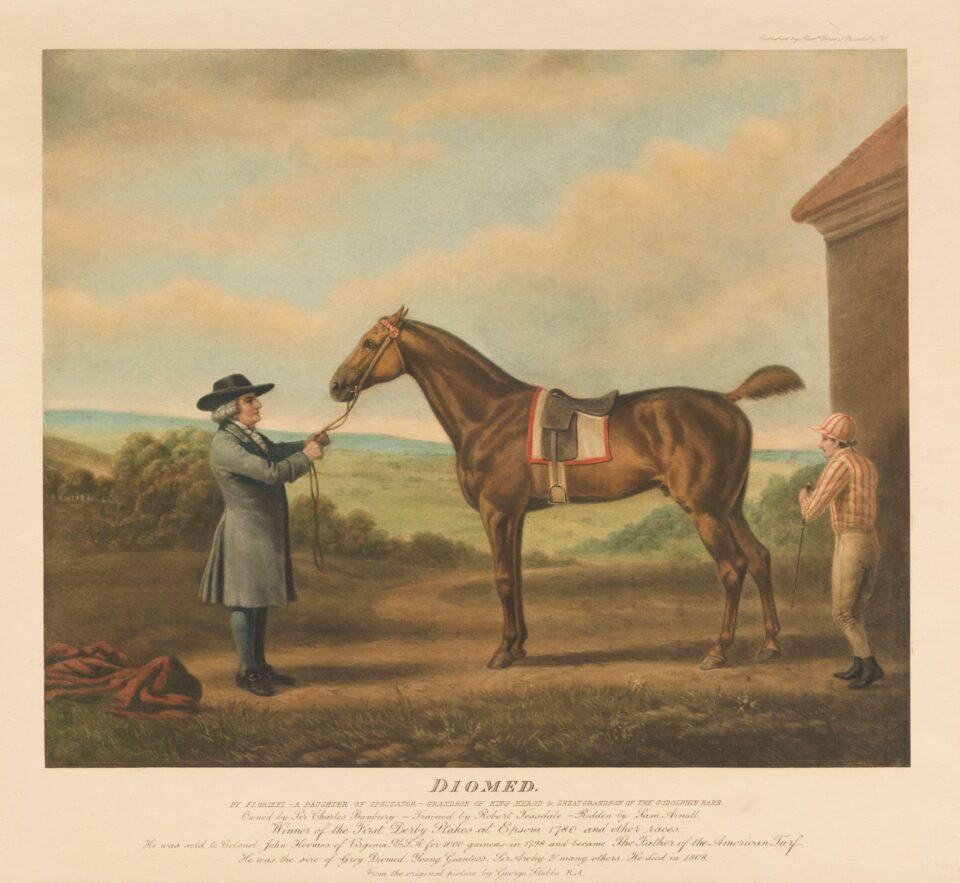

Probably the most influential broodmare of that time was Old Bald Peg, foaled around 1655. Little is known of her origins except that she was by an Arabian stallion. She bred the Old Morocco mare, dam of Spanker, said to have been the best horse in Newmarket during the reign of Charles II. Spanker, in turn, sired (fathered) the great-granddam (great-grandmother) of Flying Childers, widely regarded as the first great racehorse. Later descendants of Old Bald Peg include the first Derby winner Diomed plus 20th century Derby winner and six-time champion sire Hyperion.

1661

With the restoration of the monarchy under King Charles II in 1660, new racecourses soon appeared. Banstead Downs, near Epsom, was the first, established in 1661 (or re-established, as records suggest there may have been racing there prior to the Civil War). Diarist Samuel Pepys came to drink Epsom’s mineral spring waters in 1663 and commented “there was a great thronging to Banstead Downs, upon a great horse-race and foot-race. I am sorry I could not go thither”.

Ripon was another new venue. Races were first held on Bondgate Green in 1664, subsequently relocating to Monckton Moor.

Meanwhile, Edinburgh’s racecourse was moved from Leith to Musselburgh Links, where they raced on the sands. It was not a popular move. The ‘Sporting Magazine’ reported: “the sands at Leith where the races are held at present are in every respect so severe and ruinous to the horses and so uncomfortable for the Company that they are now almost entirely neglected even by the Scots gentry themselves.” Furthermore, as far as the country’s leading publication ‘The Scotsman’ was concerned, the course was “a reproach to the metropolis of Scotland”.

1665

Although horse racing had taken place on Newmarket Heath before the restoration, it wasn’t until afterwards that it truly came into its own. And credit for that – and horse racing in general – is due largely to King Charles II.

In 1665 (some accounts say 1664) Charles drew up conditions for a “Twelve-Stone Plate” to be run over the “New Round Course” at Newmarket on the second Thursday in October “for ever”. The Town Plate, as it was called, still takes place today, now a race for amateur riders, starting on the ‘round course’ adjacent to the National Stud and finishing up the straight of the July Course.

Nor was the Merry Monarch content with being merely a spectator. In addition to laying down the first rudimentary form of rules, occasionally acting as judge and adjudicating on disputes, he even rode in races. He also inaugurated King’s Plates, worth 100 guineas, to test and improve the resilience of the racehorse. Run over four miles with all horses carrying twelve stone, they became the most prestigious contests in the racing calendar.

Such was his enthusiasm, he was nicknamed ‘Old Rowley’ after his favourite hack, a name which has been maintained to this day with Newmarket’s Rowley Mile course.

1689

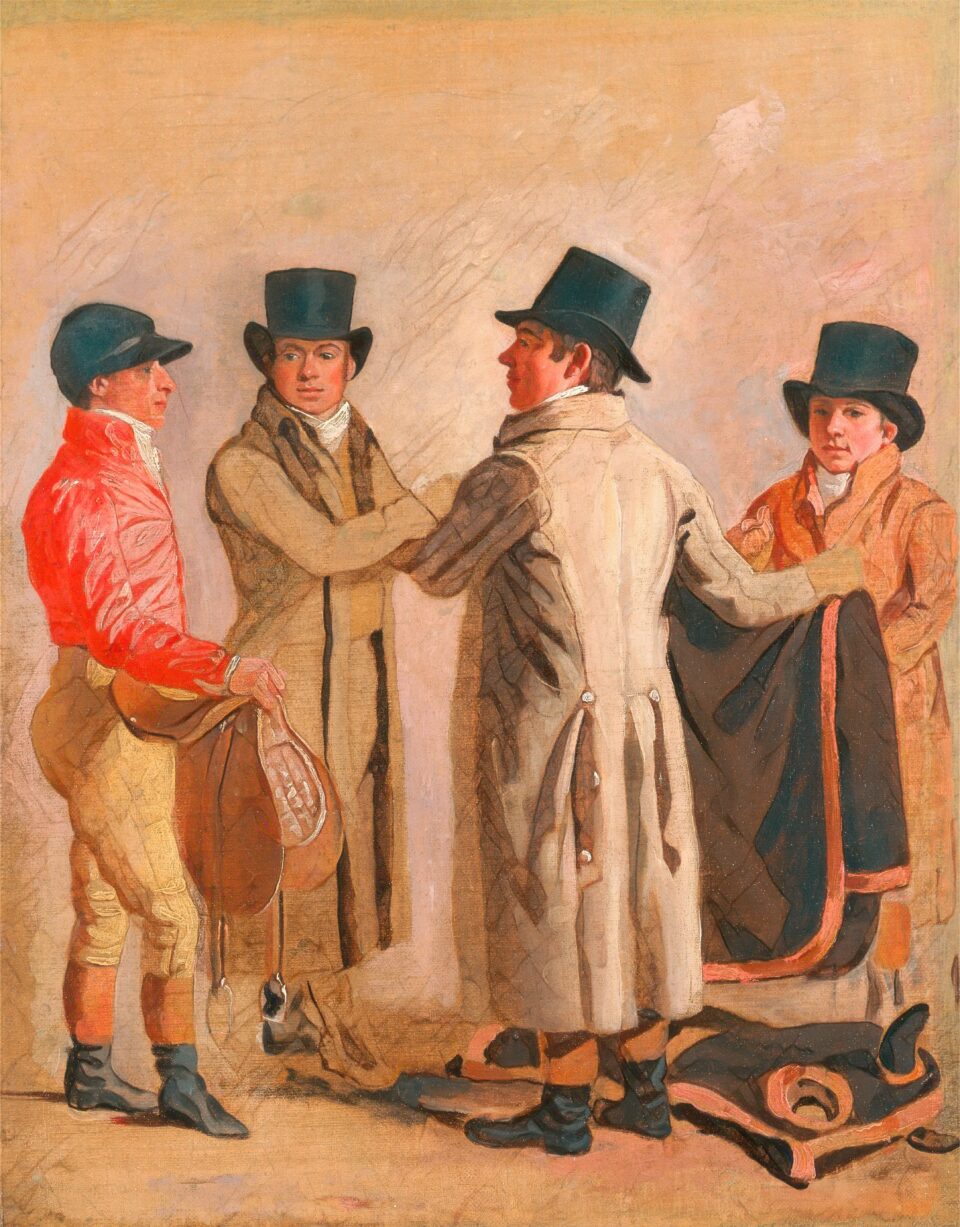

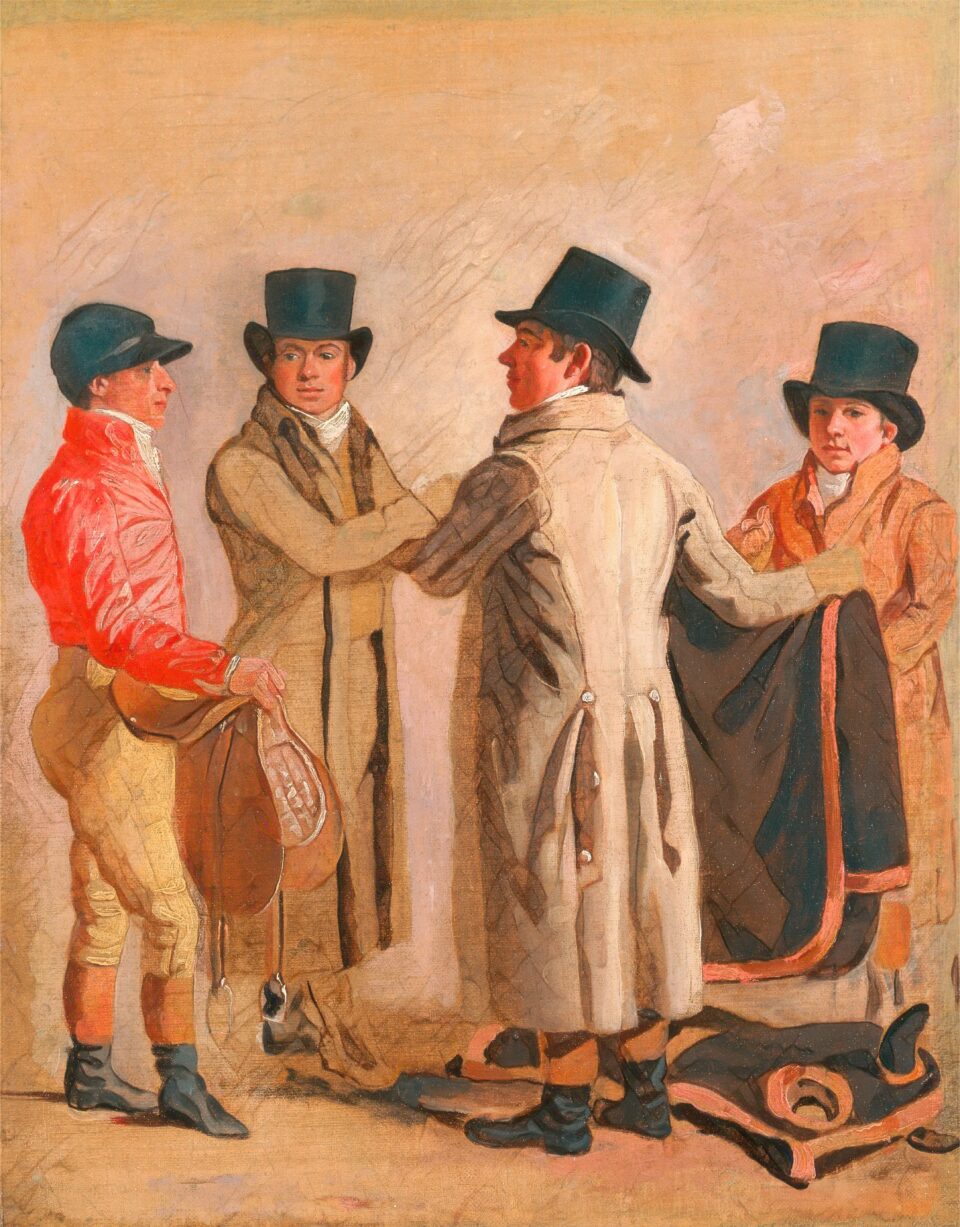

The brief, three-year tenure of Charles II’s younger brother King James II left no mark on the Turf one way or the other. However, during his reign professional jockeys were allowed to compete in races for the first time, having previously only been permitted to ride in training gallops. Prior to this, the horses had been ridden either by their owners or by the owners’ servants.

James II’s daughter Mary and her Dutch husband William III came to the throne in 1689. The pressures of defeating James II’s Jacobite troops in an attempt to recover his kingdoms at the Battle of the Boyne prevented William from devoting much time to racing during the early years of his reign, but one of his first acts – and arguably his greatest contribution to racing – was to appoint Tregonwell Frampton to the position of Keeper of the Running Horses at Newmarket, a role for which he was paid £1,000 a year.

William owned several racehorses and often bet heavily on them. On one occasion, in a £500 match, his best horse, Stiff Dick – a name unlikely to be deemed acceptable nowadays – defeated the Marquess of Wharton’s horse Careless.

1690

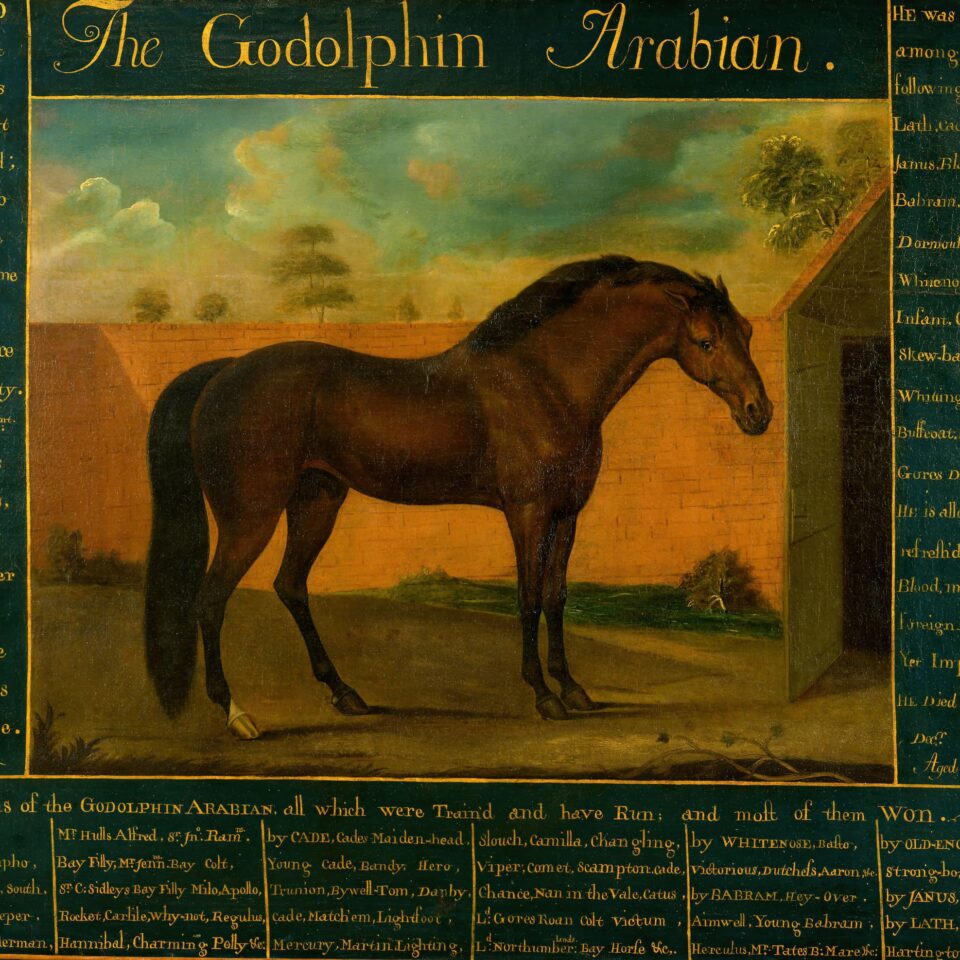

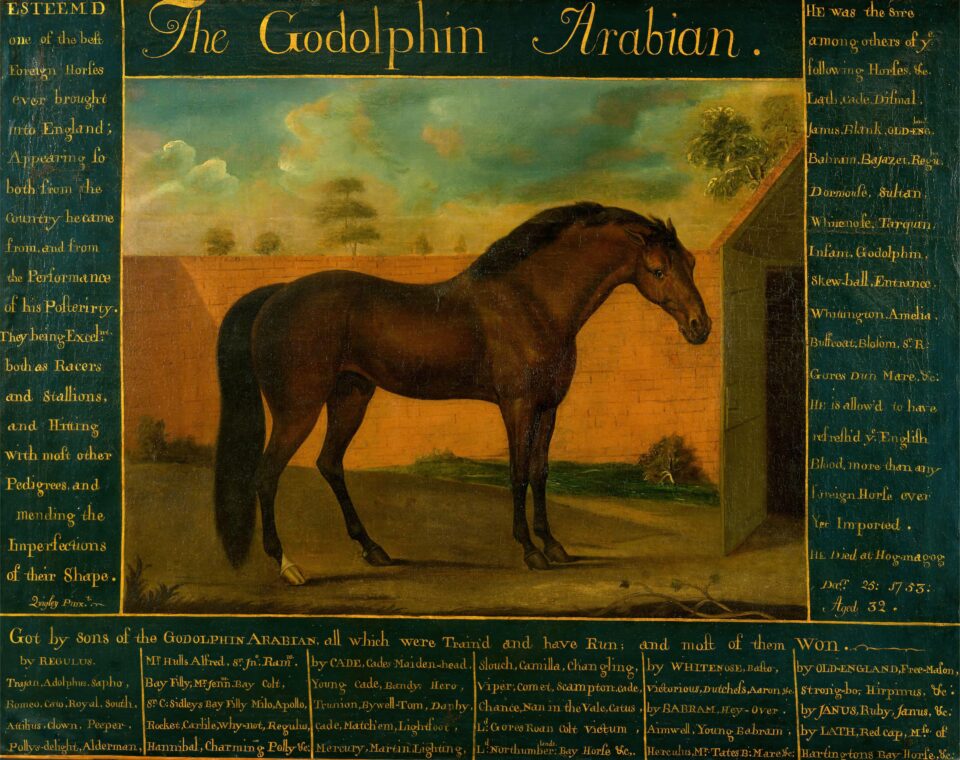

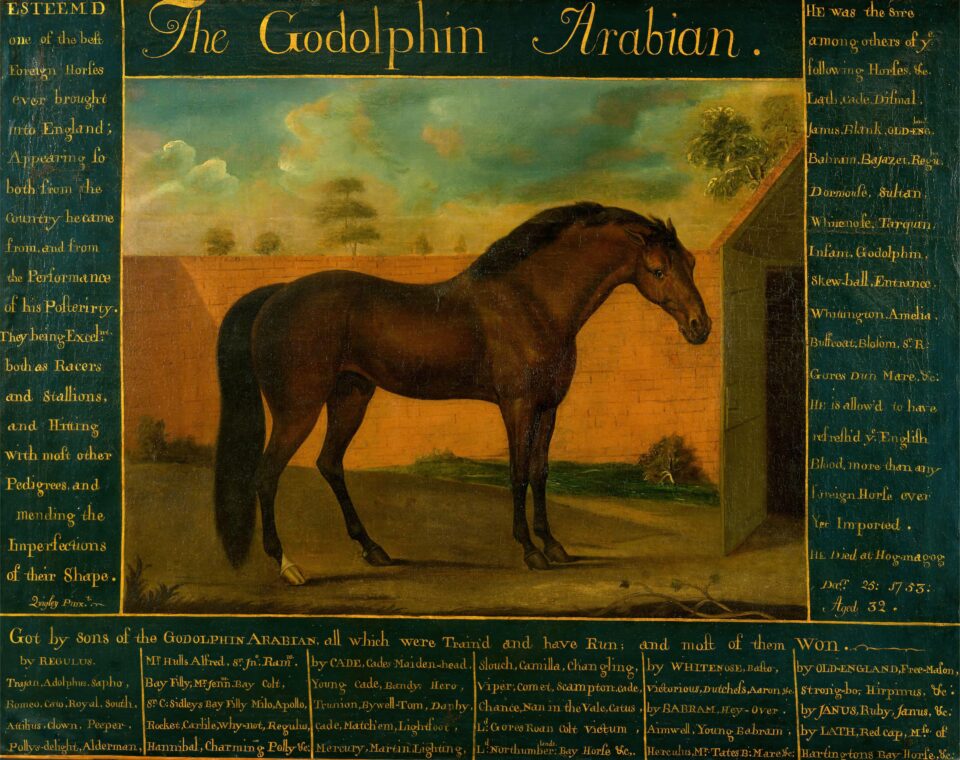

Throughout the 17th century, Galloways had been the main breed of British racehorse. The Galloway was a light but tough breed emanating from that region of south-west Scotland, usually standing between 14 and 15 hands. But the arrival of three stallions from the Middle East – the Byerley Turk, the Darley Arabian and the Godolphin Arabian – was to change all that and create the breed from which all of the world’s racehorses can be traced: The Thoroughbred.

The first to arrive was the Byerley Turk in the 1690s. Reputedly seized by Captain Byerley as a spoil of war from the Turkish army, his owner rode him in the Battle of the Boyne before standing him as a stallion at his stud in Yorkshire. Though his lineage is no longer as dominant as the two who would follow him in the early years of the 18th century, his ancestry has endured and still survives today.

The arrival of the 18th century coincided with the arrival of the Darley Arabian, whose male ancestry line is today the most prominent of the trio of foundation stallions from which all thoroughbreds are descended.

Another major development occurred on 11th August 1711 when racing began at Ascot with the running of a 100-guinea race called Her Majesty’s Plate. It may have been Queen Anne herself or her Master of the Horse, the Duke of Somerset, who identified an area of land at Ascot Common as an ideal location for a racecourse. In so doing, they laid the foundations for one of the world’s most famous horseracing venues. Queen Anne is remembered by the traditional opening race of Royal Ascot, the Group 1 Queen Anne Stakes.

That same year, ‘Give and Take’ races were introduced, the first one at Coleshill Heath, in Warwickshire. Weights and allowances were determined on a sliding scale of weight-forinches according to the height of the horse, requiring the bigger horse to carry more weight than a smaller one. Typically, the weight range was 7lb to an inch, meaning a 14-hand horse (a hand = 4 inches) would be allotted 9st (126lb) with a 15.2-hand horse having to carry 12st (168lb).

1722

Bred by Leonard Childers at Carr House, near Doncaster, and sold to the Duke of Devonshire, Flying Childers is often referred to as being the first great racehorse. However, that status is based on limited evidence, for he ran only twice, both in matches at Newmarket. In April 1721 he beat the Duke of Bolton’s Speedwell over four miles for a prize of 500 guineas. In October 1722 he beat the Earl of Drogheda’s Chanter over six miles for 1,000 guineas.

Nothing is known about the form of Speedwell or Chanter, so they cannot be used to gauge Flying Childers’ ability. His reputation stems from a four-mile trial in May 1722 – the only one ever to feature in the General Stud Book – against a horse called Fox, a winner of three King’s Plates, the Ladies Plate at York and several matches. Flying Childers gave Fox a stone (14lb) in weight and beat him by a distance estimated at 360 yards over the ‘Long Course’ at Newmarket.

He retired to stud at the Duke of Devonshire’s Chatsworth home but, unlike his year younger full-brother Bartlet’s Childers, did not found an enduring male line.

1748

The first recorded race for four-year-olds took place at Hambleton, Yorkshire, in 1727. That same year saw the first publication of John Cheney’s ‘An Historical List of all Horse Matches and of all Plates and Prizes run for in England and Wales (of the value of £10 and upwards)’.

The Godolphin Arabian, the third of the trio of the thoroughbred’s foundation stallions, arrived in England around 1730. His most notable sons included the brothers Lath and Cade, both out of the mare Roxana. Lath was the better racehorse but Cade proved the better stallion and was the sire of Matchem, one of the greatest stallions of the 18th century.

Foaled in 1748, Matchem was bred by John Holme in Carlisle and sold to William Fenwick of Bywell, Northumberland. He was a decent though not outstanding racehorse, winning eight races between 1753 and 1758, including the Ladies Plate at York and two races at Newmarket. But he surpassed those achievements after being retired from racing and sent to Fenwick’s Bywell stud. He was leading sire three years running from 1772 to 1774. He lived to the great age of 33 and it is through Matchem that the Godolphin Arabian’s line survives today.

1752

A racing milestone occurred in 1752 with the foundation of the Jockey Club. Its influence was initially confined to Newmarket but it gradually became the adjudicator and governance of racing throughout the country. By the end of the century the Jockey Club had attained such authority that it felt powerful enough to tell the Prince of Wales to dismiss his jockey.

Regarding its title, several owners in that period still rode their horses in matches and the word ‘jockey’ denoted an owner as much as a rider. The word ‘club’ also had a wider sense and applied to any particular group of friends that met at regular intervals to discuss matters of common interest.

George II’s third son, William, Duke of Cumberland, was an early member of the Jockey Club. His greatest contribution to racing, though, would be as the breeder of both Herod and Eclipse. Herod, foaled in 1758, was among the best racehorses of his time. At stud his most important son was the unbeaten Highflyer (1774-1794), bred by Sir Charles Bunbury. Highflyer sired three Derby winners and helped perpetuate the Byerley Turk line. Bunbury was also the Jockey Club’s most eminent figure and its first ‘public face’.

1764

Racing colours were first registered at Newmarket in 1762. The next famous horse to carry them was Gimcrack. Foaled in 1760, he was no bigger than a pony, measuring just over 14 hands. His size proved a big advantage in ‘Give and Take’ races, in which weights were allotted according to a horse’s size, winning five such contests. He made his debut at Epsom on 31st May 1764, when beating five opponents for a £50 prize. Between then and 1771 he won 26 of his 36 starts. Gimcrack had six different owners during his racing career including Sir Charles Bunbury.

Gimcrack was retired to stud at Oxcroft Farm, near Newmarket, in 1772 at a fee of 25 guineas. He did not cover many mares, his lack of popularity probably being explained by his diminutive size. He is commemorated today by the Group 2 Gimcrack Stakes at York, founded in 1846. Ironically, Gimcrack only ran twice at York and was beaten both times.

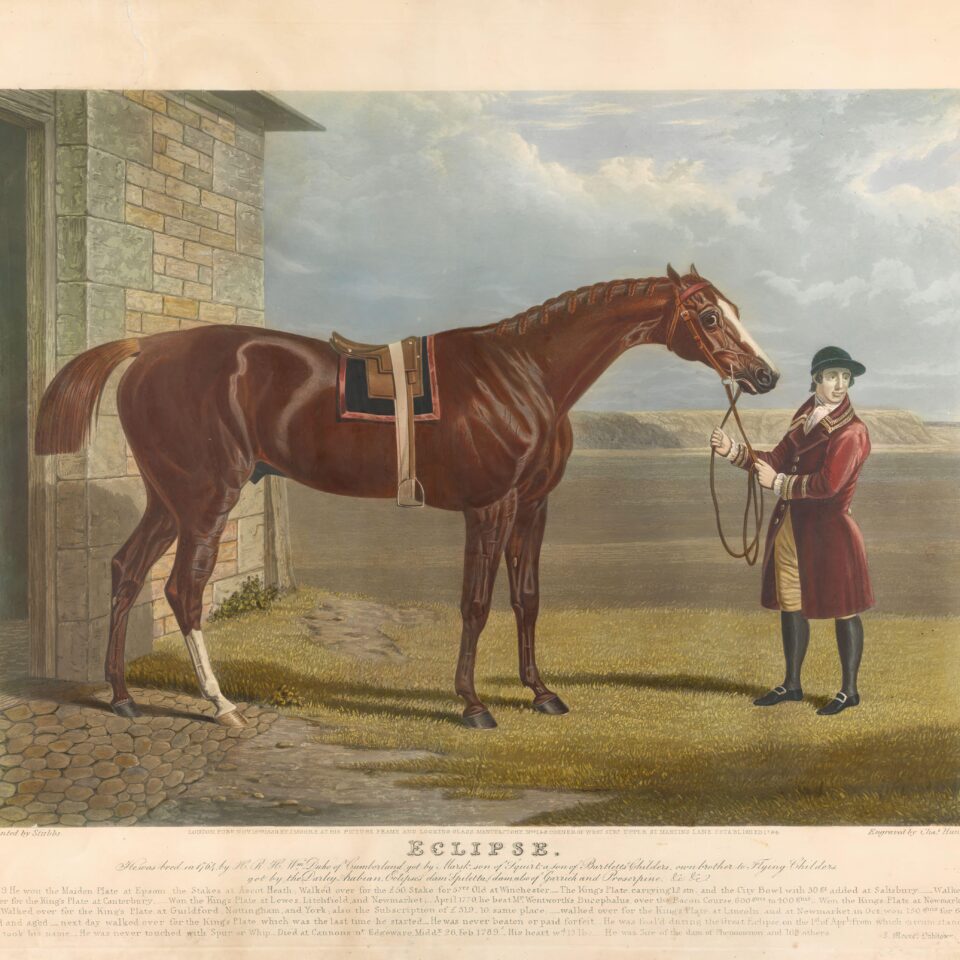

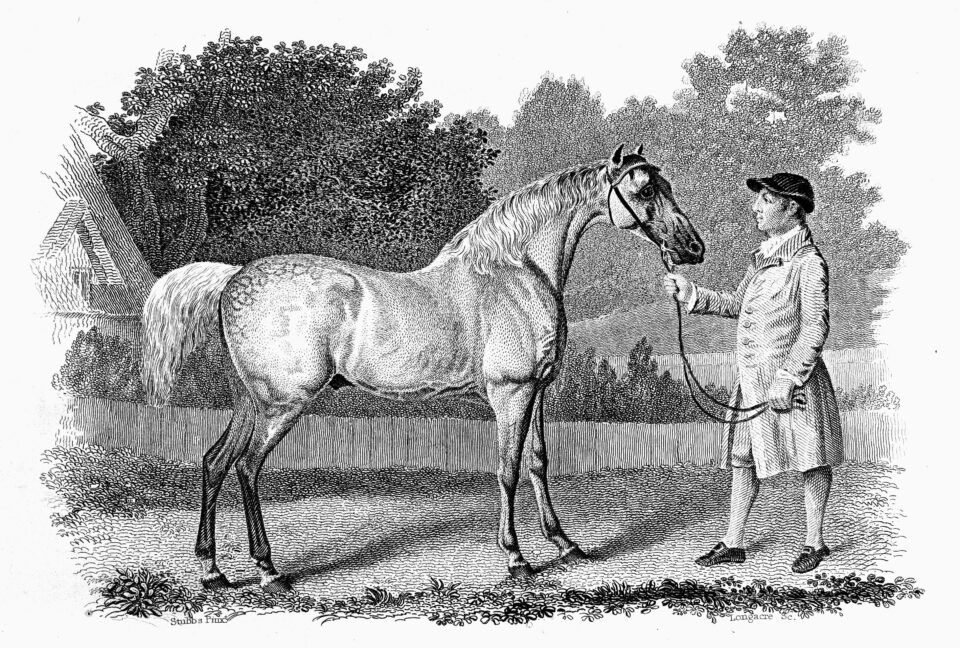

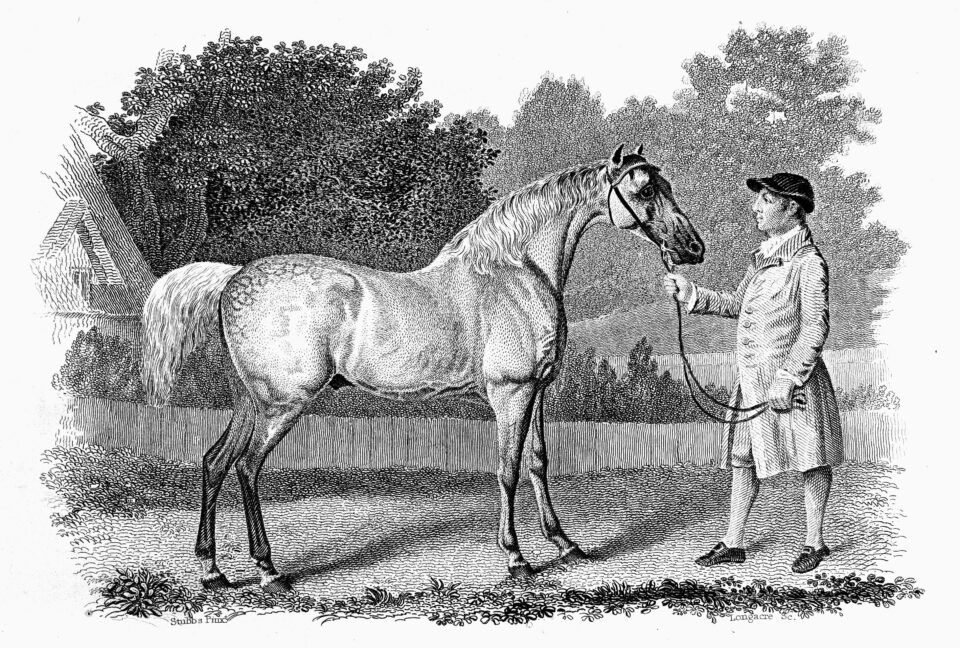

George Stubbs (1724-1806), widely acclaimed as Britain’s greatest equine artist, painted Gimcrack on Newmarket Heath. The painting hangs in the Jockey Club rooms at Newmarket. Stubbs also famously painted Eclipse, born in 1764, the second truly great racehorse in the history of the Turf.

1776

In 1773, James Weatherby, whose official title was Keeper of the Match Book at Newmarket, published the first volume of the Racing Calendar. This was duly followed by the first Stud Book, containing pedigrees of all horses that had run in races for the previous 50 years.

Three-year-old races had become ever more popular by the 1770s. In 1776 a group of sporting gentlemen, including the Marquis of Rockingham and Colonel Anthony St Leger of Park Hill, drew up conditions for a race for three-year-olds, over two miles, to be run at Doncaster’s racecourse at Cantley Common. It was won by an unnamed filly of Lord Rockingham’s, later called Alabaculia. It was not until the race’s third running in 1778 – the first year it was run on Doncaster’s new Town Moor course – that it was named, at Rockingham’s suggestion, after the popular Colonel St Leger.

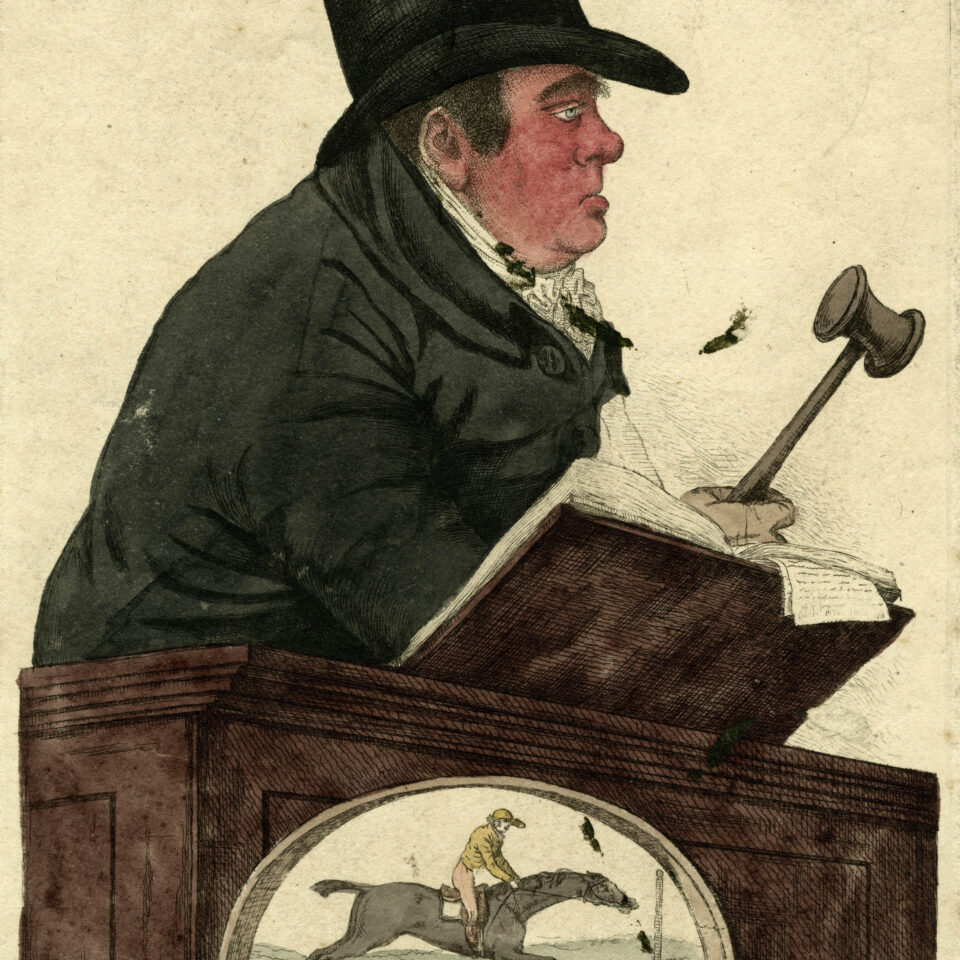

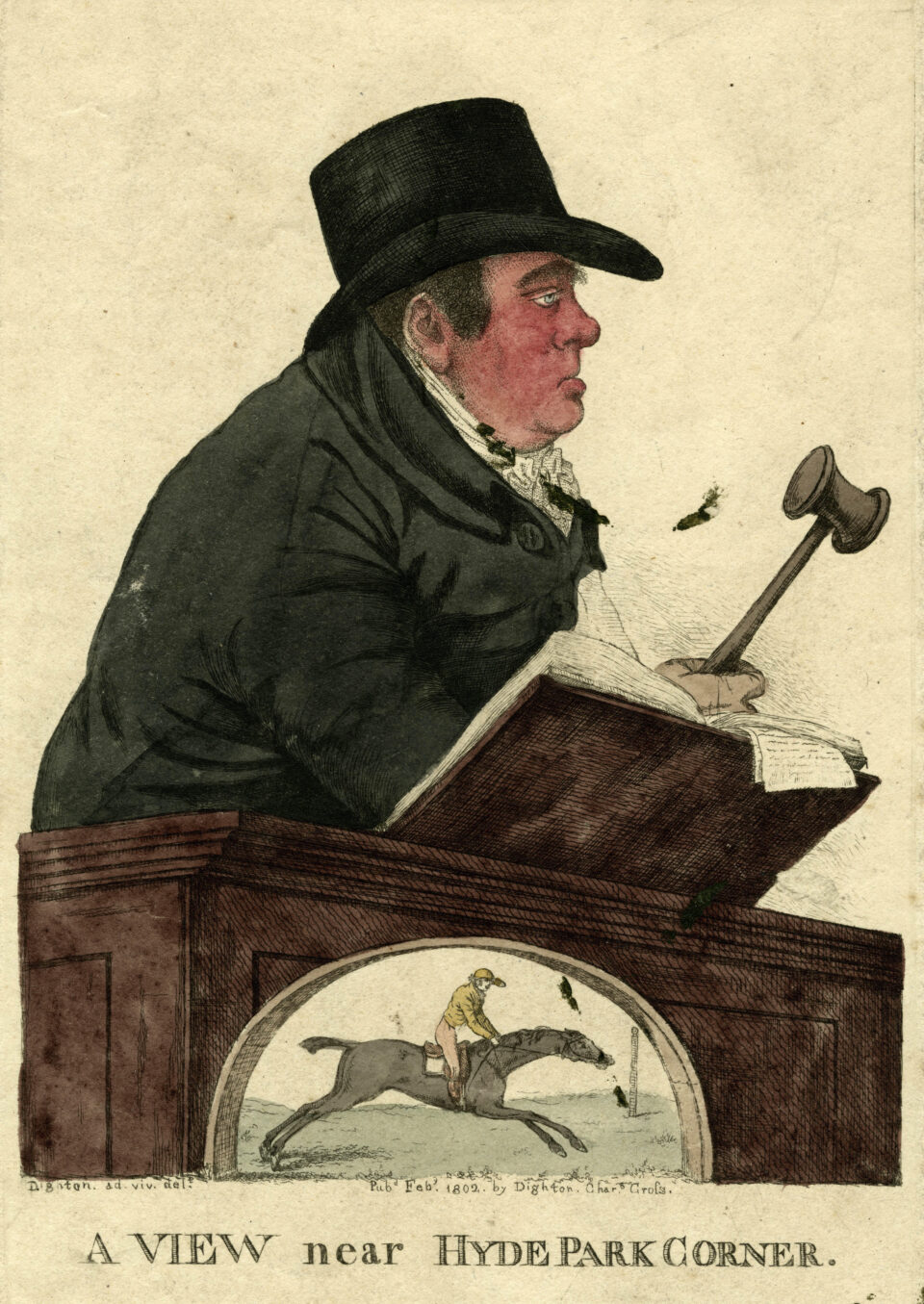

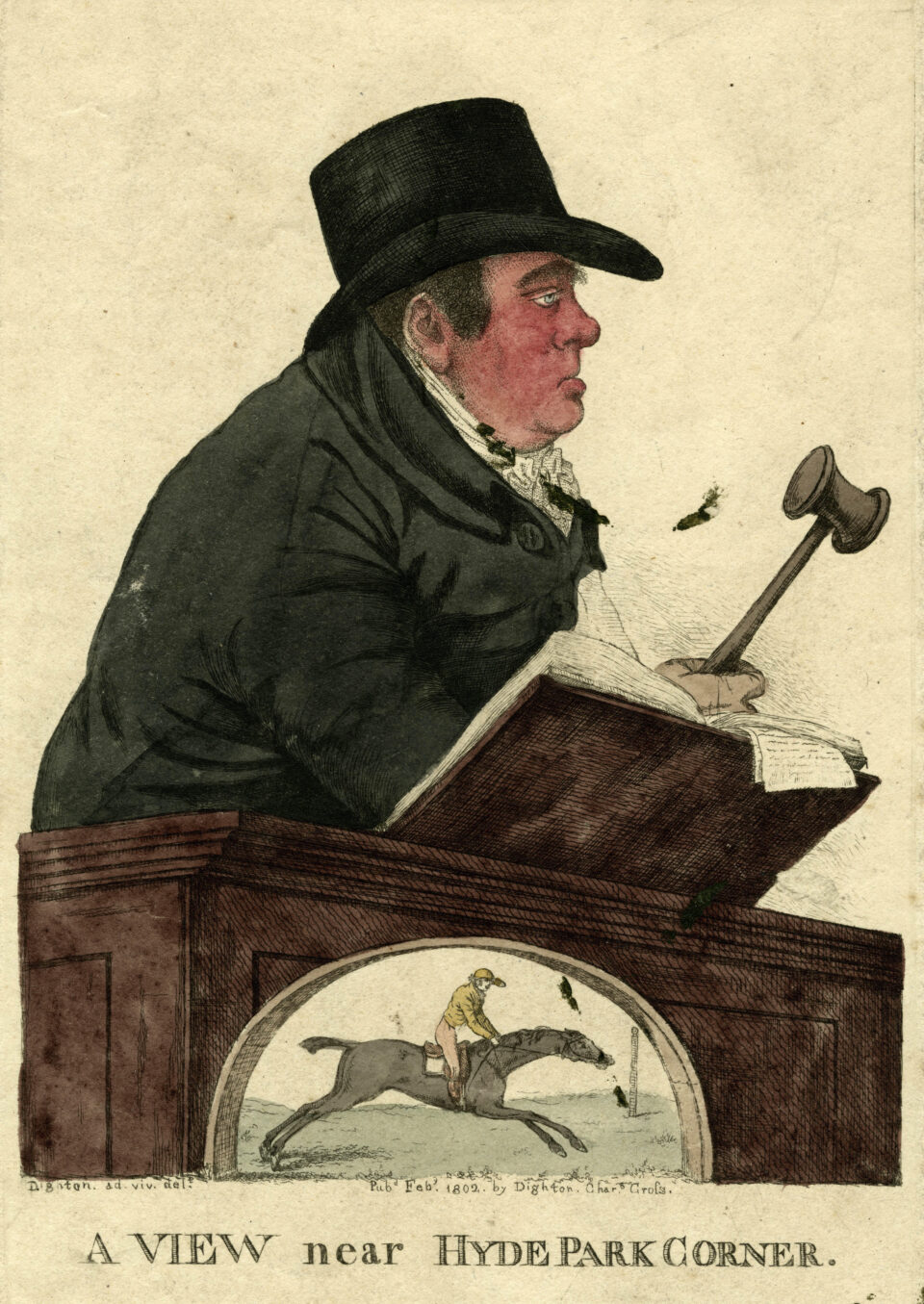

Doncaster’s Group 2 Park Hill Stakes, named after Colonel St Leger’s estate, is popularly known as the fillies’ St Leger. Meanwhile, Richard Tattersall had founded an auction company and was holding regular horse sales at London’s Hyde Park Corner. Today, Tattersalls, now based at Newmarket, is Europe’s leading bloodstock auctioneer, selling 10,000 horses a year.

1780

The 12th Earl of Derby, a keen racing man, had bought a converted inn near to Epsom’s racecourse called The Oaks from his uncle General Burgoyne. During a party at The Oaks in 1778, Lord Derby and his friends planned a three-year-old race, for fillies only, to be run the following summer and to be called the Oaks after Lord Derby’s estate. Appropriately, Derby won the inaugural running himself with a filly named Bridget.

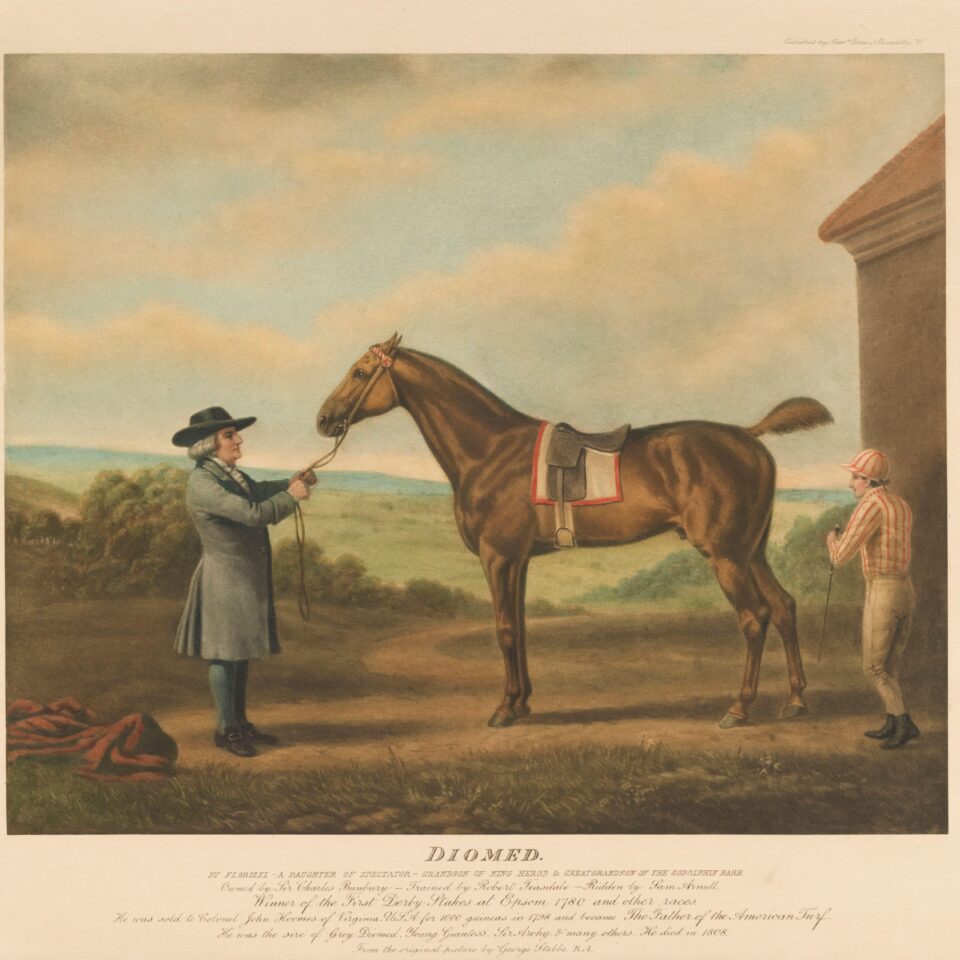

At a subsequent gathering at The Oaks, spurred on by the success their race, a second threeyear- old contest was agreed for the following year, this one for colts and fillies, over a mile (the race’s distance was increased to a mile and a half in 1784). Sir Charles Bunbury was among those present. According to legend – probably apocryphal – a coin was tossed to decide whether the race should be named in honour of Bunbury or Derby. Sir Charles supposedly lost the toss but won the first running of the Derby in 1780 with his horse Diomed, the 6-4 favourite, ridden by Sam Arnull. The race was deemed of no great importance and there is no record of how far Diomed beat the runner-up, 4-1 second favourite Budrow.

1791

Two-year-old races began in the south of England in the 1770s and were well established by the mid-1780s. The July Stakes, run today at Newmarket’s July Meeting, is the oldest such race still in existence, dating from 1786.

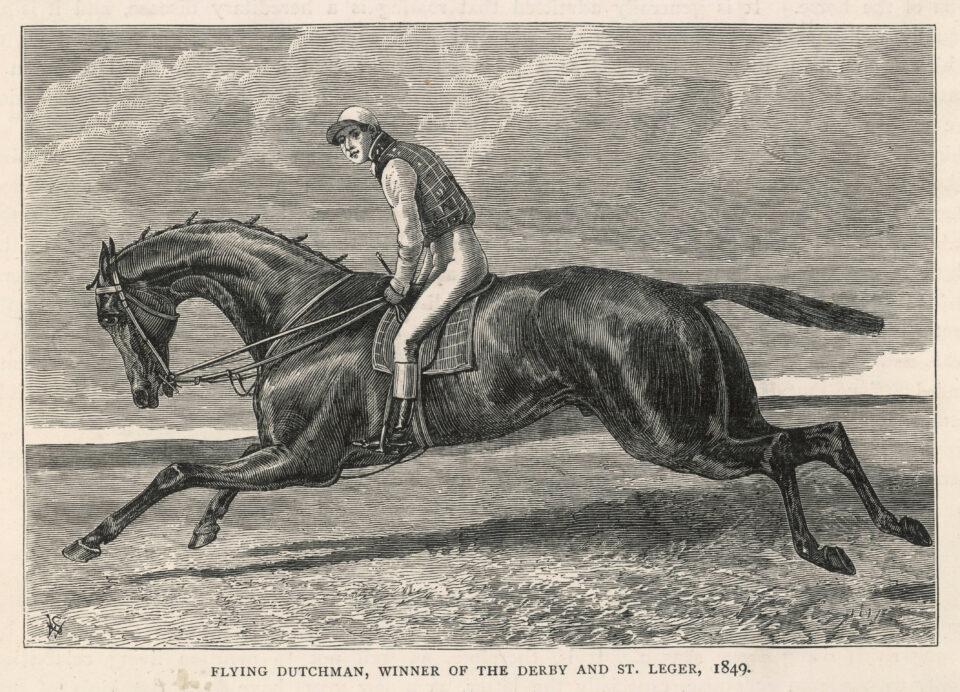

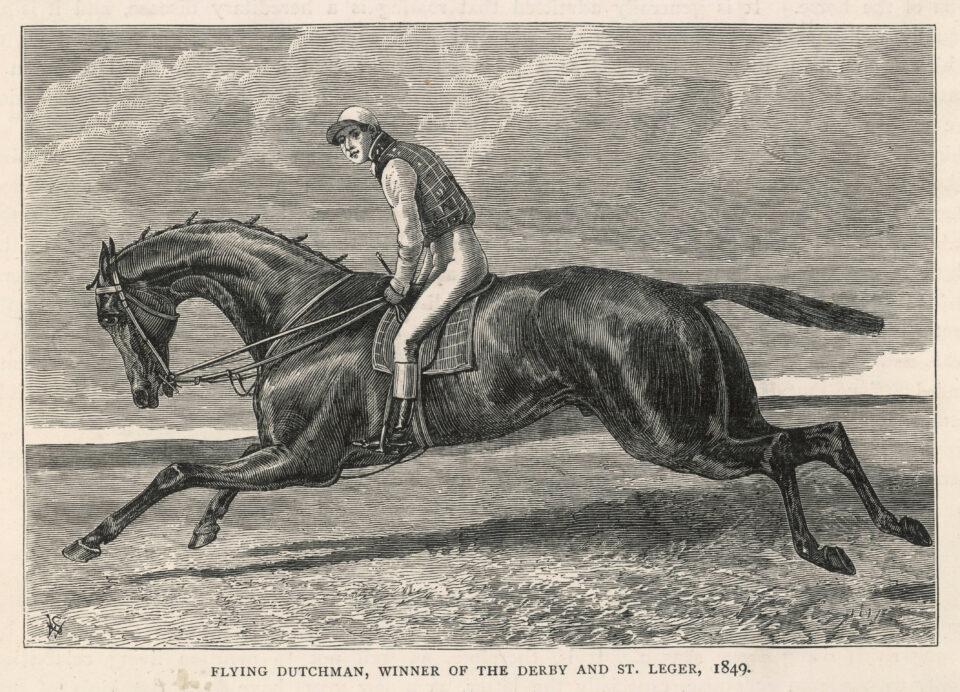

The race’s original conditions stipulated that horses sired by Eclipse or Highflyer must carry 5lb extra. Some of its early winners bore unappealing names such as Ostrich, Duckling, Joke and even Loo. Nowadays it tends to be dominated by precocious types but its list of winners reveals some famous names including Derby winners The Flying Dutchman and Donovan and the great quadruple classic-winning filly Sceptre.

The first important handicap race, the Oatlands Handicap, took place in June 1791 at Ascot. The weights were allocated according to horses’ form to give them a theoretical equal chance. The weights ranged from 5st 11lb to 9st 10lb (73lb to 136lb). A field of 19 – enormous for the time – went to post in front of a crowd of 40,000. The Prince of Wales, son of King George III, was determined to win it and entered four horses, one of whom, Baronet, carrying 8st 4lb and ridden by the leading jockey Sam Chifney, duly obliged at 20-1.

1791

That was also the year of the notorious ‘Escape affair’. On Thursday, 20 October 1791 the Prince of Wales ran his six-year-old Escape, ridden by Sam Chifney, in a four-horse race over two miles at Newmarket. Escape started at 2-1 on and finished last. He was brought out again the next day for a race over four miles on Newmarket’s Beacon Course, again ridden by Chifney. Due to his poor showing the day before, his starting price was 5-1. This time he won easily, beating two of the horses from the previous day’s race. He was backed by the Prince and also by Chifney (jockeys were permitted to bet in those days).

The Stewards of the Jockey Club, who included Sir Charles Bunbury, interviewed Chifney, who told them that, in his opinion, the horse had not been fully fit for his first race and needed the run. The Stewards took a different view and duly informed the Prince that if Chifney rode his horses again at Newmarket, “no gentleman would start against him.”

The upshot was that the Prince stood by Chifney, severed his connection with Newmarket and vowed never to set foot there again.

1792

Chifney was one of several jockeys to make their mark during the last two decades of the 18th century. Among them was Sam Arnull (1760-1800) who won the first running of the Derby on Sir Charles Bunbury’s Diomed. He also rode for Lord Derby, for whom he won the 1787 Derby on Sir Peter Teazle and the 1794 Oaks on Hermoine. He also won the Derby for two other owners, in 1782 on Assassin and in 1798 on Sir Harry.

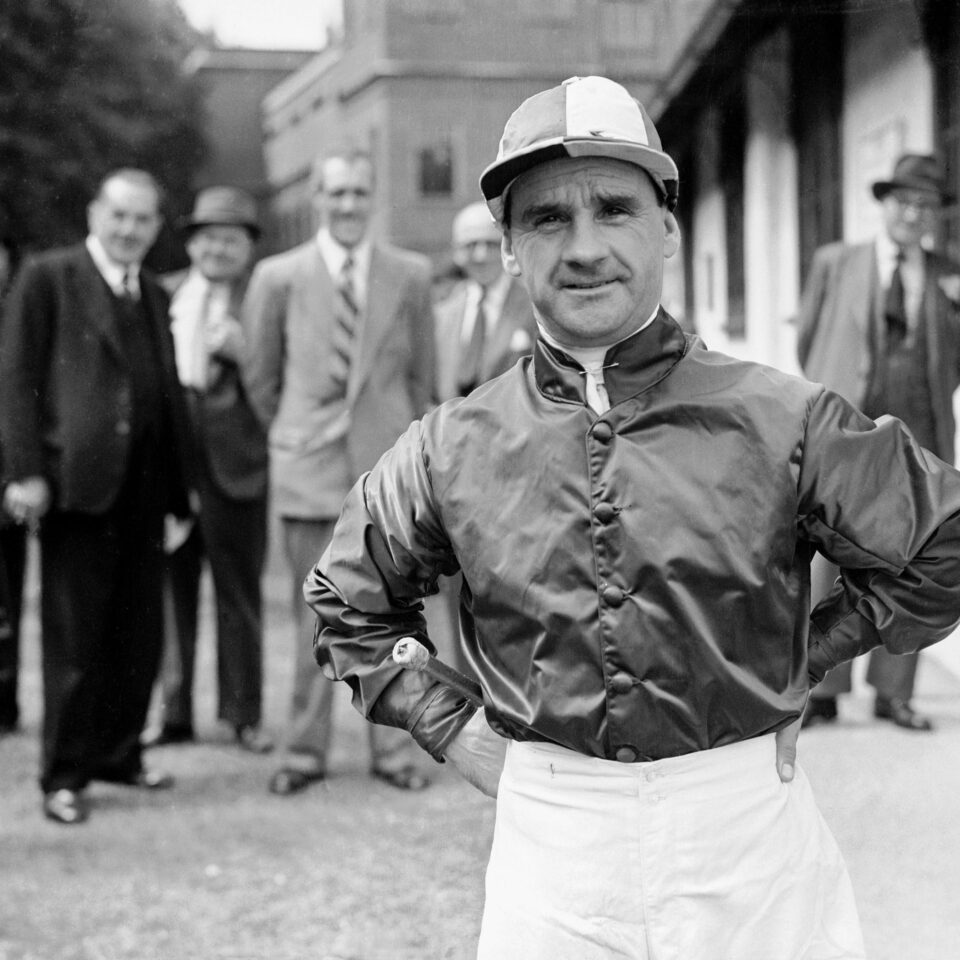

Another famous jockey was John Singleton (1776-1802) who, though born in France, hailed from a Yorkshire racing family. He was only 17 when winning the 1791 Oaks on the Duke of Bedford’s Portia. He won the Oaks again two years later on another of the Duke’s fillies. Caelia, and also won the 1797 Derby for him on the unnamed colt by Fidget. But arguably the best of them all, Chifney included, was Frank Buckle (1766-1832), whose total of 27 classic winners – the first of them in 1792 – has been surpassed only by Lester Piggott. Moreover, in an age noted for corruption, Frank Buckle’s unquestioned honesty brought respectability to race-riding.

The 19th century dawned with King George III in his 41st year as reigning monarch, and his son, the Prince of Wales, having effectively severed connections with Newmarket following the notorious ‘Escape affair’ of 1791. It heralded a period that would see the number of British racecourses double during the first half of the century, while the number of horses in training would treble.

Racing began at Goodwood in 1801 on a course laid out by the 3rd Duke of Richmond. It was initially a low-key, single-day affair comprising races for hunters, a far cry from today’s five day ‘Glorious’ extravaganza on the Sussex Downs. The Ascot Gold Cup was first run in 1807 and won by a three-year-old named Master Jockey, beating three opponents. The race was worth 100 guineas and took place in the presence of King George III, Queen Charlotte and their children. Master Jockey was trained by Richard Prince who, four years later, would be in the headlines for a very different reason, being the innocent victim of a notorious case of horse doping.

In 1811, four of Prince’s horses died after drinking from a horse trough on Newmarket Heath that had been poisoned with arsenic. A local tout named Daniel Dawson was accused of poisoning the trough after a medical dispenser at Guy’s Hospital named Cecil Bishop had turned king’s evidence and implicated him. Dawson was tried at Cambridge Assizes and found guilty. He was hanged on 8th August 1812. Meanwhile, the bookmakers who were widely believed to have been behind the doping escaped without censure.

1827

The trend of running younger horses over shorter distances continued. The inaugural running of the 2,000 Guineas had taken had taken place in 1809 and the first 1,000 Guineas followed in 1814.

Nonetheless, there was still an ample supply of reliable veterans who turned up year after year, none more so than Dr Syntax, who, in 1821 won the Preston Gold Cup for a record seventh consecutive year. Born in 1810 and standing less than 15 hands, Dr Syntax was the most popular horse trained in the North. In addition to his seven Preston Gold Cups, he won 29 other races including the Richmond Gold Cup and the Lancaster Gold Cup five times each. He retired to stud at the age of 12 and sired (fathered) Ralph, winner of the 1841 2,000 Guineas, the 1842 Cambridgeshire and the 1843 Ascot Gold Cup.

In 1825 King George IV instituted the Royal Procession at Ascot. On the Tuesday of the meeting, the King arrived in a dark green coach pulled by four horses, giving birth to a tradition that has been maintained to this day.

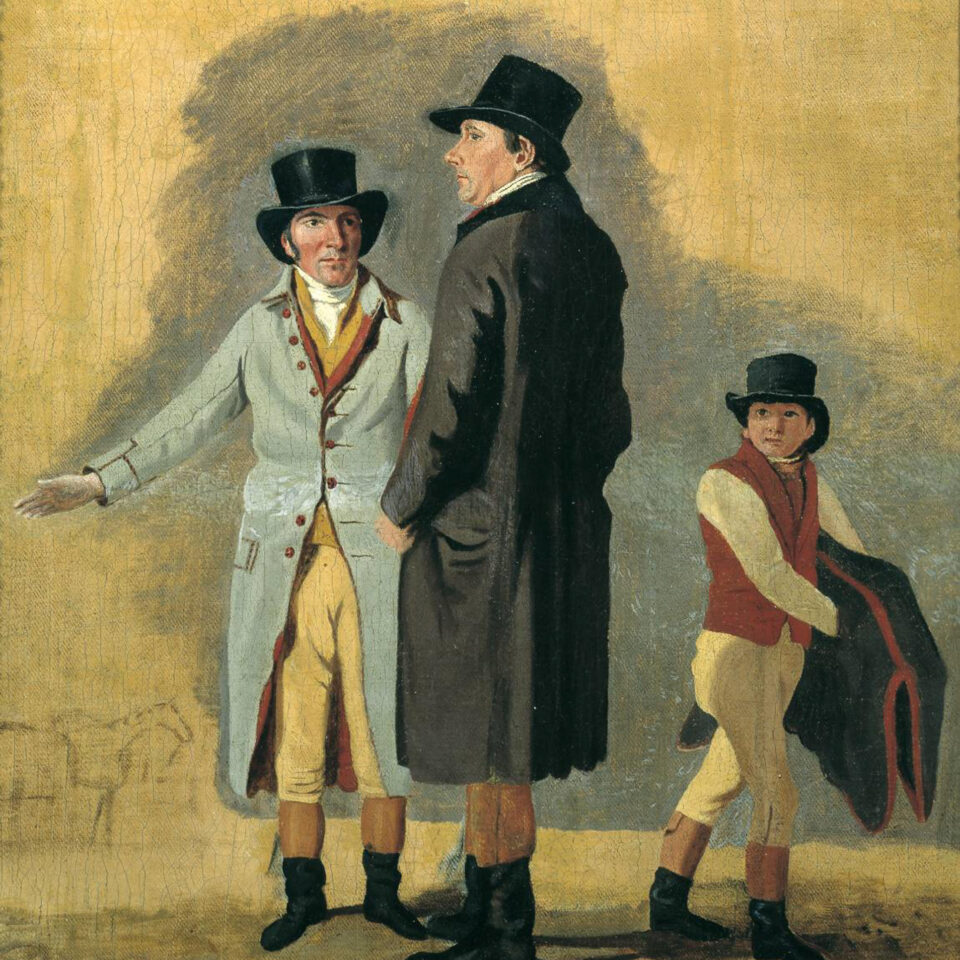

The greatest trainer of the first quarter of the 19th century was Robert Robson, who trained 33 Classic winners, including seven of the Derby. Between 1819 and 1827 he won the 1,000 Guineas eight times and the 2,000 Guineas five times for his main owner, the Duke of Grafton.

1836

The first dead-heat in the history of the Derby occurred in 1828. There was a re-run between the two dead-heaters, with Cadland prevailing by a neck from The Colonel, giving jockey Jem Robinson his fifth Derby winner. He won his sixth and last Derby on Bay Middleton in 1836, a record which stood until Lester Piggott equalled (and later surpassed) it in 1972. Bay Middleton had not been entered for the St Leger. In his absence, Elis, owned by Lord George Bentinck, was installed ante-post favourite. Bentinck considered Elis’s odds far too short, so he hatched a plan to obtain a bigger price.

In those days, the only option was to walk horses to the course at which they were to race. A week before the St Leger, Elis was still in his box at Goodwood. The bookmakers knew that he wouldn’t have time to walk to Doncaster, so they pushed out his price. What they didn’t know was that Bentinck had built the world’s first horsebox to convey Elis to Doncaster. Elis was loaded onto the vehicle and covered the 250-mile journey in just three days, the wagon being drawn by a relay of horses. He won the St Leger with ease and Bentick landed his bets.

1844

The 1844 Derby produced a scandal which, due to the determination of Lord George Bentinck, was eventually exposed. The name of the first horse past the post was Running Rein. In fact, it was a four-year-old called Maccabaeus.

The real Running Rein was sold as a foal to a disreputable gambler named Abraham Goodman. Maccabaeus had been bought by Goodman as a yearling. The changeover took place in 1842. The following year the new Running Rein was sold to the unsuspecting Alexander Wood, an Epsom corn merchant. When Running Rein (really Maccabaeus) made a winning debut in a two-year-old race at Newmarket, he looked what he was, a well-grown three-year-old. Throughout the winter Goodman backed him for the Derby while a suspicious Bentinck amassed evidence as to the horse’s real identity.

Bentinck warned the Epsom stewards that he believed Running Rein to be a four-year-old. However, they decided to allow him to start and to hold an inquiry if he won, which he did by three-quarters of a length from Colonel Jonathan Peel’s colt Orlando.

Various legal actions followed, the upshot being that Running Rein was found to be four and disqualified, the race being awarded to Orlando. Goodman had fled the country, leaving Wood to carry the can. Summing up, the Judge remarked that “if gentlemen condescended to race with blackguards, they must condescend to expect to be cheated”. Orlando provided multiple champion jockey Nat Flatman with his sole Derby victory.

1855

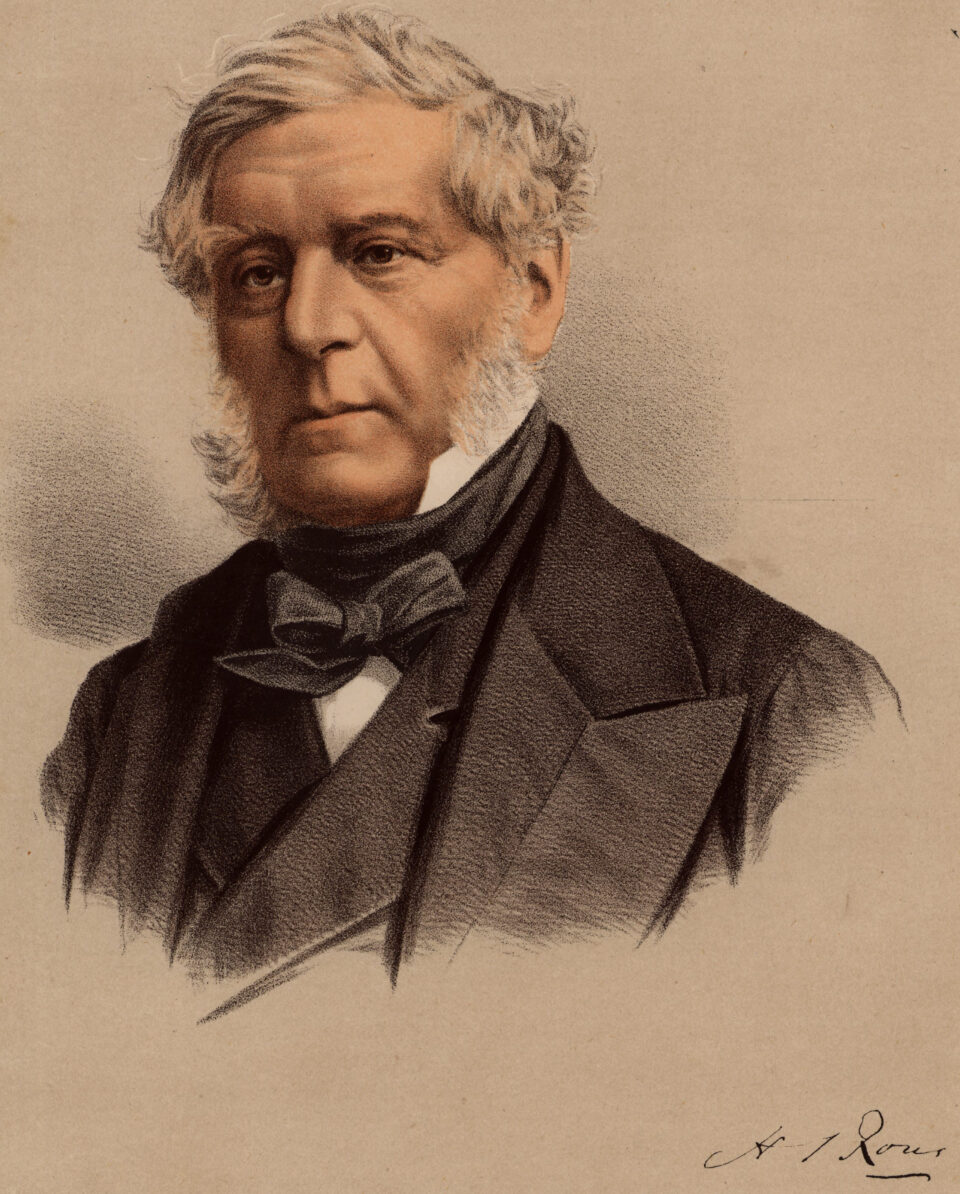

The 1850 Derby was won by Voltigeur, scoring by a ‘comfortable length’. He should have won the St Leger just as easily but dead-heated after being badly hampered. He duly won the runoff. Two days later, ridden by Nat Flatman, Voltigeur reappeared and beat the previous year’s Derby and St Leger winner The Flying Dutchman in the Doncaster Cup. The Flying Dutchman carried 8st 12lb and was conceding 19lb to Voltigeur. They met again the following May in a match race over two miles at York with The Flying Dutchman giving 8½lb to Voltigeur, their respective weights having been determined by Admiral Henry Rous, Steward of the Jockey Club. This time The Flying Dutchman got his revenge, winning by a ‘short length’. Ironically, although The Flying Dutchman won that match, it is Voltigeur whose name is commemorated at York each August by the Group 2 race at the Ebor meeting.

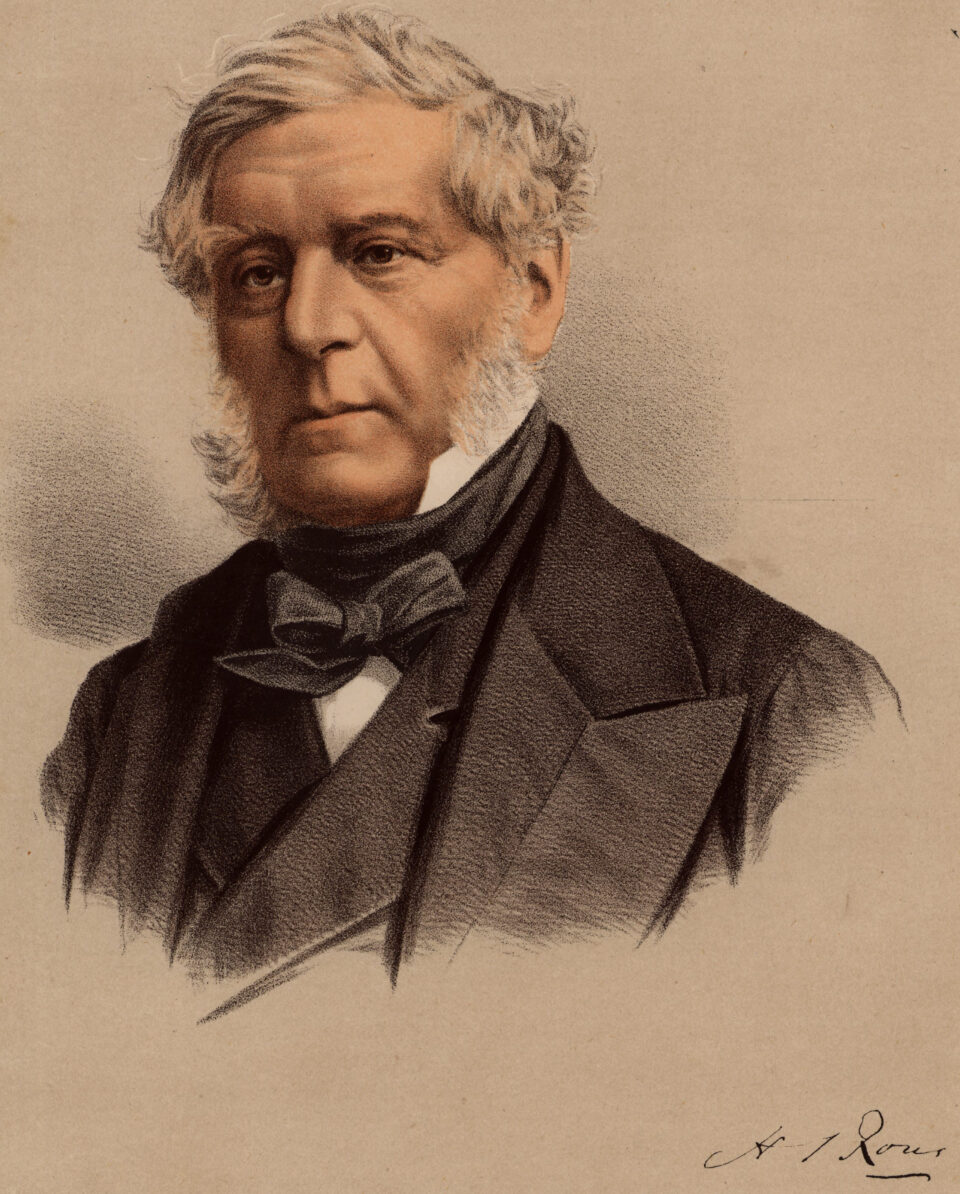

In 1855, Admiral Rous was given the post of horseracing’s official handicapper. His prestige grew throughout the 1850s, emerging in the 1860s as the third great ‘Dictator of the Turf’.

1857

Malton-based John Scott was the dominant northern trainer during the mid-19th century. He trained for 46 seasons and saddled a total of 40 Classic winners between 1827 and 1863 (14 of them ridden by his brother William), a record that stood alone for more than 150 years until equalled by Aidan O’Brien in 2021.

Scott won the Derby five times, the Oaks eight times and a remarkable 16 St Legers. He trained the first Triple Crown winner, West Australian, in 1853, ridden by Frank Butler, who had succeeded William Scott as stable jockey. Butler had also won the previous year’s Derby for Scott on Daniel O’Rourke. However, by that time he was struggling to keep his weight down and was forced to retire at the end of 1853, having ridden a total of 14 Classic winners.

Scott’s main rival at Malton was William I’Anson. He bred, owned and trained Blink Bonny, the second of just five fillies to have won both the Derby and the Oaks at Epsom. She was a 20-1 shot when winning the 1857 Derby, adding the Oaks two days later. At stud she produced three foals, the second of which, Blair Athol, won the Derby and St Leger for I’Anson.

1858

Numerically, the stars of the mid-19th century were the fillies Alice Hawthorn, who won 52 of her 79 starts including the Chester, Goodwood and Doncaster Cups; and Catherina, winner of 79 of her 176 races. Catherina’s record is all the more impressive in that many of those contests were run in heats. She actually faced the starter 208 times and came home first on 136 occasions.

Another top-class filly was Virago. During her three-year-old season, she won the Great Metropolitan and City and Suburban handicaps on the same afternoon, then won the 1,000 Guineas, two races at York, the Nassau Stakes, Goodwood Cup, Warwick Cup and Doncaster Cup. Of the colts, Fisherman won 70 of his 121 starts including two Ascot Gold Cups, while Rataplan ran 71 times and scored 42 victories, 19 of them in one season.

As of 1858, the date from which all British racehorses changed their age was moved from 1st May to 1st January. This had been the case for horses trained at Newmarket since 1834 but, at long last, the rest of the country followed suit.

1868

In 1864, the politician Count Frédéric de Lagrange became the first French owner to win an English classic when his filly Fille de l’Air won the Oaks. He also owned Gladiateur, who became the second Triple Crown winner in 1865. Both horses were trained by Tom Jennings at Newmarket.

Known as the ‘Avenger of Waterloo’, Gladiateur was the first French-bred horse to win the Derby. Following his Newmarket and Epsom triumphs, Gladiateur annexed the Grand Prix de Paris and two races at Goodwood before winning the St Leger. He remains the only horse to have won the British Triple Crown and the Grand Prix de Paris.

The outstanding filly of the 1860s was Formosa, who won four Classics. Having dead-heated for the 1868 2,000 Guineas, she then won the 1,000 Guineas, Oaks and St Leger. In the first three of those she was ridden by George Fordham. Among the most famous jockeys of the 19th century, Fordham was by then on the way to winning the 12th of his 14 champion jockey titles.

1879

During the 1870s, the number of racecourses declined but the decade saw the opening of the new ‘park’ courses at Sandown (in 1875) and Kempton (1878). These were the first ‘enclosed’ courses whereby the public had to pay to get in. This generated significant revenue from the turnstiles, enabling the racecourse owners to offer enhanced prize money, improved facilities and a higher quality of racing. Sandown also invented the ‘club’ system, with a members’ enclosure, creating an environment suitable for female racegoers. The policy proved so successful that, just 11 years after its opening, Sandown was able to introduce the Eclipse Stakes, Britain’s first £10,000 race, its inaugural running being won by Bendigo, the mount of Tom Cannon.

The standard of these new courses proved so high that most of the bad and disreputable ones were soon forced out of business. Another reason for their demise was a rule that came into effect in 1877 stating that each course must add a minimum of £300 to each day’s prize money. The following year the Jockey Club went a step further by decreeing that no race should be worth less than £100 to the winner. In 1875 the Jockey Club issued a new set of rules for jockeys. They were no longer allowed to own racehorses or to bet. Other innovations introduced by the Jockey Club included, in 1877, rules for determining the draw for starting positions. In 1879 it became compulsory for all jockeys to be licensed.

1886

John Osborne was the most popular and successful northern-based jockey during the second half of the 19th century. He rode for 46 years, winning 12 Classics – he was 55 when landing his last Classic victory. Nicknamed ‘The Bank of England Jockey’ in tribute to his honesty, he later trained and continued to ride work on Middleham Moor until within a year of his death, aged 89.

But by far the most famous jockey of the Victorian era was Fred Archer. Champion 13 years in succession from 1874 to 1886, he rode 2,748 winners and partnered the two greatest horses of the 19th century, St Simon and Ormonde. He won 21 Classics including the Derby five times, the third of which, Iroquois in 1881, was the first American-bred horse to win it.

Although he never ran in a Classic, St Simon was arguably the greatest horse Archer rode. He was never beaten or even extended in nine races. However, Ormonde also holds a legitimate claim for the title of the 19th century’s greatest racehorse. Archer rode both of them and marginally preferred St Simon, but there were many who thought otherwise. Ormonde’s trainer, John Porter, had reason to be biased but commented: “I do not think we ever saw his equal as a racehorse.”

1899

In 1894 the Earl of Rosebery owned the 2,000 Guineas and Derby winner Ladas, trained by Mat Dawson, thus becoming the first – and so far, only – British Prime Minister to win a Derby while in office. He won it again the following year with Sir Visto. There was a royal Derby winner in 1896, Persimmon, bred and owned by the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII).

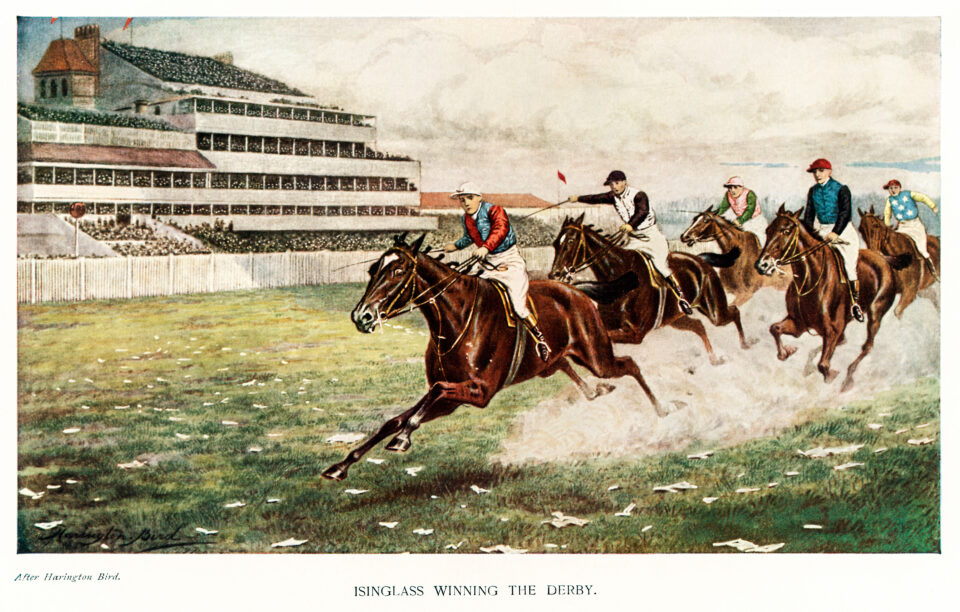

The 1890s was a vintage era for Triple Crown winners. Common (1891), Isinglass (1893), Galtee More (1897), and Flying Fox (1899) all won the 2,000 Guineas, Derby and St Leger, while La Fleche (1892) captured the fillies’ version of the 1,000 Guineas, Oaks and St Leger.

Three of those – Common, La Fleche and Flying Fox – were trained by John Porter, the greatest trainer of the last quarter of the century. His other top-class horses included Isonomy, sire of both Isinglass and Common. Isonomy did not run in any of the classics but was at his peak as a four-year-old, winning the Ascot Gold Cup, Goodwood Cup, Brighton Cup, Ebor Handicap and the Doncaster Cup. The following season he won the Manchester Cup and the Ascot Gold Cup for the second time.

Of all the 1890s Triple Crown winners, Isinglass was the finest. He confirmed his greatness as a four-year-old when outclassing his opponents in the Eclipse Stakes, beating that year’s Derby winner Ladas in a canter. He won the following year’s Ascot Gold Cup on his sole start at five, retiring the winner of 11 of his 12 starts, worth a total of £57,455, an amount that remained a British record until surpassed by Tulyar in 1952.

Isinglass was ridden to his Triple Crown, Eclipse and Gold Cup victories by Tommy Loates, while Flying Fox was the mount of Mornington Cannon. Loates rode 1,426 winners and was champion jockey three times, while Cannon won six jockeys’ titles during the 1890s along with seven Classics. Loates and Cannon both rode in the traditional British style with long stirrups and sat upright in the saddle. However, that would soon change, due primarily to the arrival in the closing years of the century of American jockey James Foreman ‘Tod’ Sloan, whose crouching ‘monkey up a stick’ style was initially derided by the racing community. But when Sloan rode 108 winners from 345 rides on 1899 – a 31% strike rate – they were forced to take notice.

Twentieth-century horseracing could not have got off to a better start with the Prince of Wales (soon to become King Edward VII) winning the 2,000 Guineas, Derby and St Leger in 1900 with Diamond Jubilee, thus becoming the only member of the Royal Family to win the Triple Crown. For good measure, he also won that year’s Grand National with Ambush II. To date, he is the only person to have owned a Grand National winner and a Triple Crown winner in the same year.

Diamond Jubilee, a full-brother to the Prince’s 1896 Derby winner Persimmon, was a badtempered sort and the only person who could humour him was his lad, Herbert Jones. Thus, it was the then virtually unknown Jones who guided Diamond Jubilee to Triple Crown glory. He would later take over as the royal jockey.

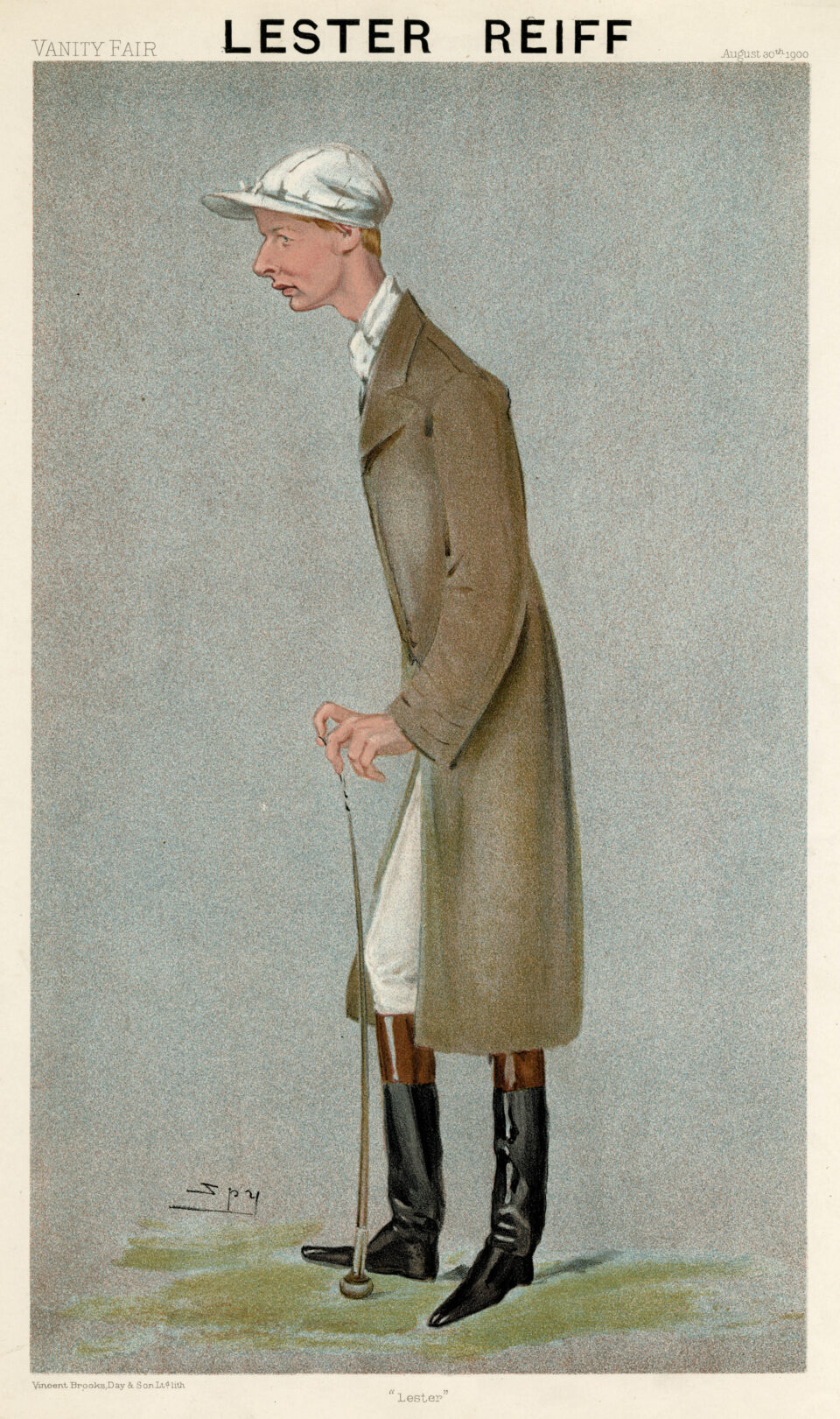

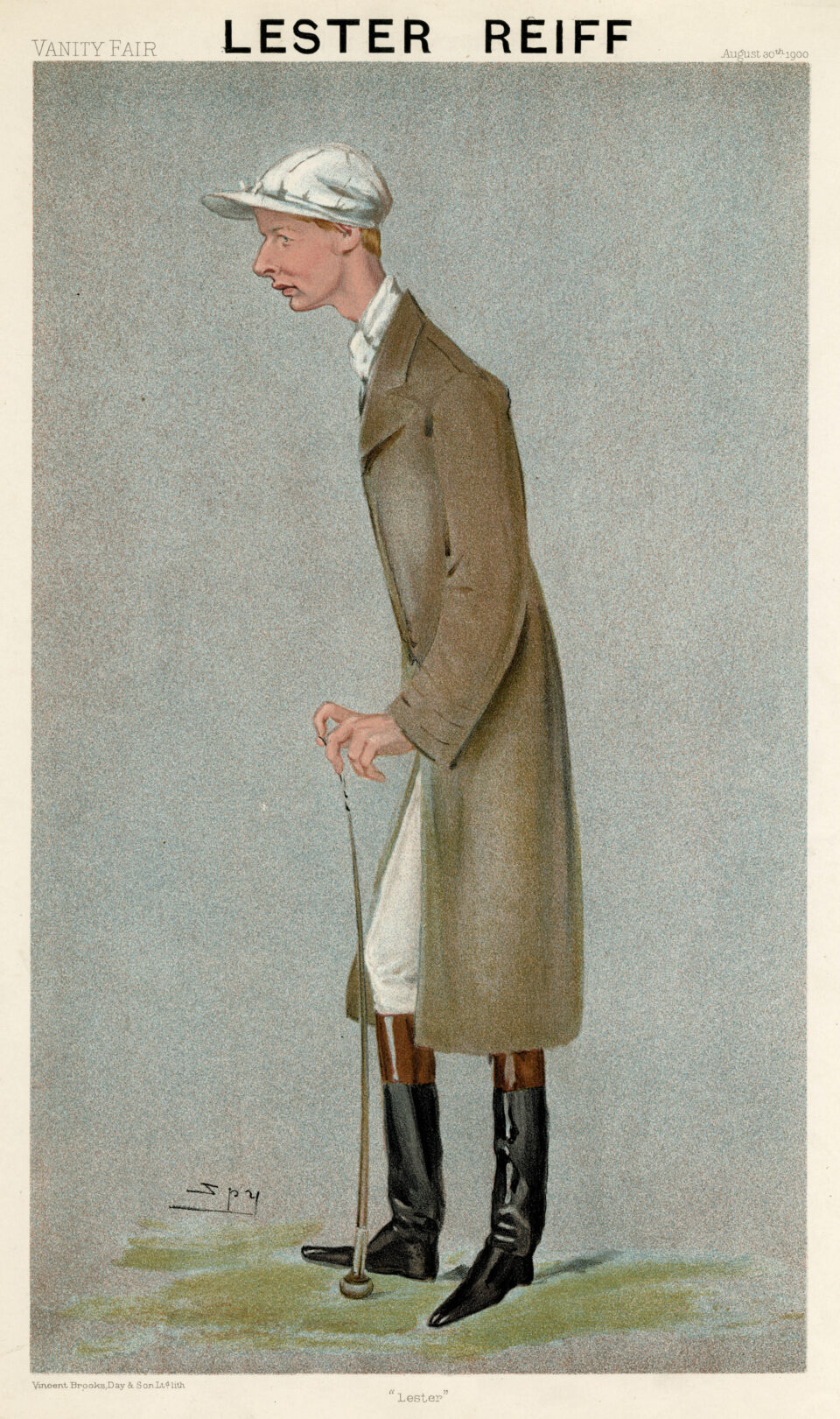

The invasion of American jockeys reached its climax in 1900. Four of them, ‘Skeets’ Martin, Danny Maher and the Reiff brothers, Lester and Johnny, had followed Tod Sloan to England and were soon in great demand. The Reiffs had almost 1,200 rides between them in 1900. The end of the season saw Lester crowned champion jockey with 143 wins with Johnny in third place. Five of that year’s top ten jockeys were American.

1901

In 1901 Lester Reiff became the first American jockey to win the Derby, guiding 5-2 favourite Volodyovski to victory. But his days in British racing were numbered. Later that season he was warned off for allegedly ‘stopping’ a horse at Manchester’s September meeting. A similar fate had effectively befallen Tod Sloan the previous year. He admitted to betting on horses and was advised that his licence would not be renewed.

It wasn’t only American jockeys who were making their presence felt; it was American trainers too. They brought about a revolution in training methods, almost as radical as the jockeys had influenced riding styles with their low, crouched seats. American trainers believed in giving their horses short, sharp work, rather than over long distances. Their stables were airier with open doors and windows, and their feeding regimens were far more scientific.

American trainer John Huggins trained the Derby winner Volodyovski, while another, Enoch Wishard, had brought over the Reiff brothers. Wishard and his fellow countrymen were shrewd trainers but there was also an unseemly side, in that it was common knowledge they regularly doped their horses with cocaine.

1902

‘Skeets’ Martin became the second American jockey to win the Derby when guiding Ard Patrick to a three-length victory in 1902. The even-money favourite Sceptre finished fourth.

The Derby was the only Classic that eluded Sceptre, one of the greatest fillies in racing history. She won the 2,000 Guineas in record time, turning out two days later to win the 1,000 Guineas, despite a twisted plate. Only an ill-judged ride by her jockey Herbert Randall, who was in his first year as a professional after riding as an amateur, prevented her from winning the Derby.

Two days later she won the Oaks in effortless style, going on to add the St Leger, beating Derby runner-up Rising Glass by three lengths.

It was not all plain sailing for Sceptre that year, due to the unorthodox methods of her owner Robert Sievier, who had taken over her training following the decision of Charles Morton, who had trained Sceptre as a two-year-old, to become private trainer to Jack Joel.

Despite Sceptre having won four classics, the hard gambling Sievier was still short of money at the end of the season and was obliged to sell her the following year.

1903

The 1903 Derby fell to an American jockey for the third successive year when Danny Maher brought odds-on favourite Rock Sand home two lengths clear of the French colt Vinicius. Rock

Sand had already won the 2,000 Guineas in the hands of fellow American ’Skeets’ Martin and went on to complete the Triple Crown by winning the St Leger.

Rock Sand started favourite for that year’s Eclipse Stakes but proved no match for the four-year-olds Ard Patrick and Sceptre. In an early contender for the race of the century, Ard Patrick beat Sceptre by a neck, with Rock Sand three lengths further back in third.

While doping was not then a criminal offence, by 1903 it had become scandalous. It took the initiative of trainer George Lambton to bring about a change of rules. Lambton informed the Jockey Club Stewards that he intended to dope five of his horses, none of whom had shown any worthwhile form. Lambton’s experiment worked exactly as he thought. When four of them won and the other finished second, the Jockey Club was forced to take action and outlaw the practice. Doping was banned by the end of the year and any transgressors were warned off.

1904

Ard Patrick had been ridden to that famous Eclipse Stakes victory over Sceptre and Rock Sand by Otto Madden, who claimed the last of his four champion jockey titles in 1904.

Born in Germany of English parents, Madden was apprenticed initially to James Waugh and then Richard Marsh, for whom he won the 1898 Derby on 100-1 outsider Jeddah (the first 100-1 Derby winner). Previous to 1904, he had been champion jockey in 1898, 1901 and 1903.

Madden retired in 1909 and took up training, only to return to the saddle during the First World War due to the shortage of jockeys. That enabled him to win a wartime substitute Oaks on Sunny Jane before relaunching his training career.

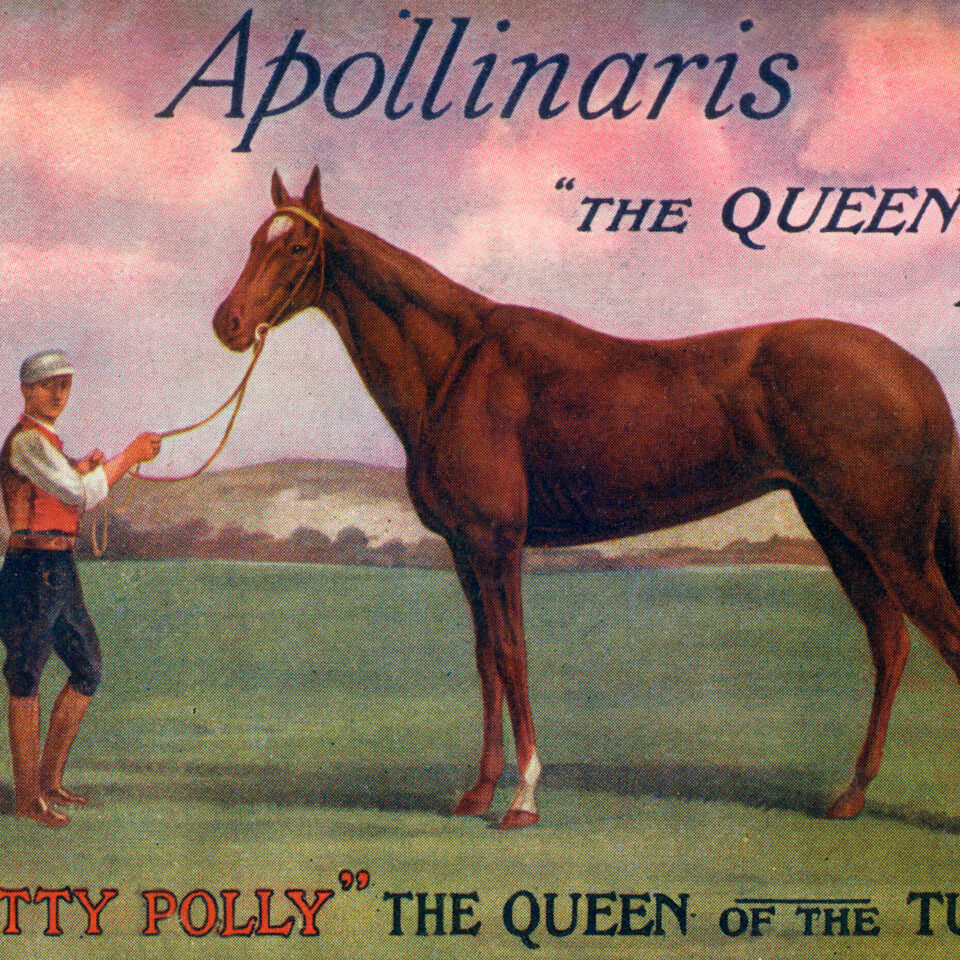

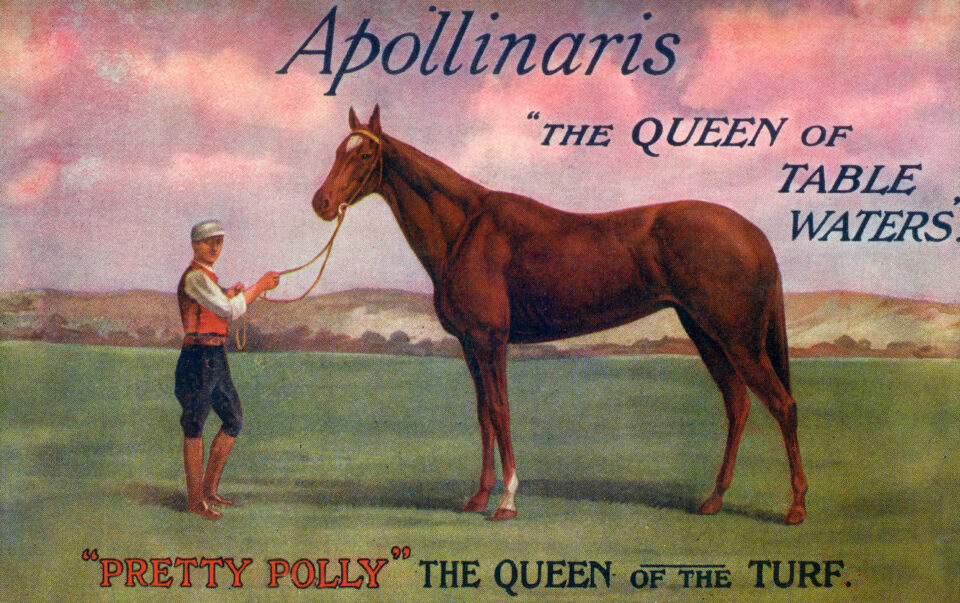

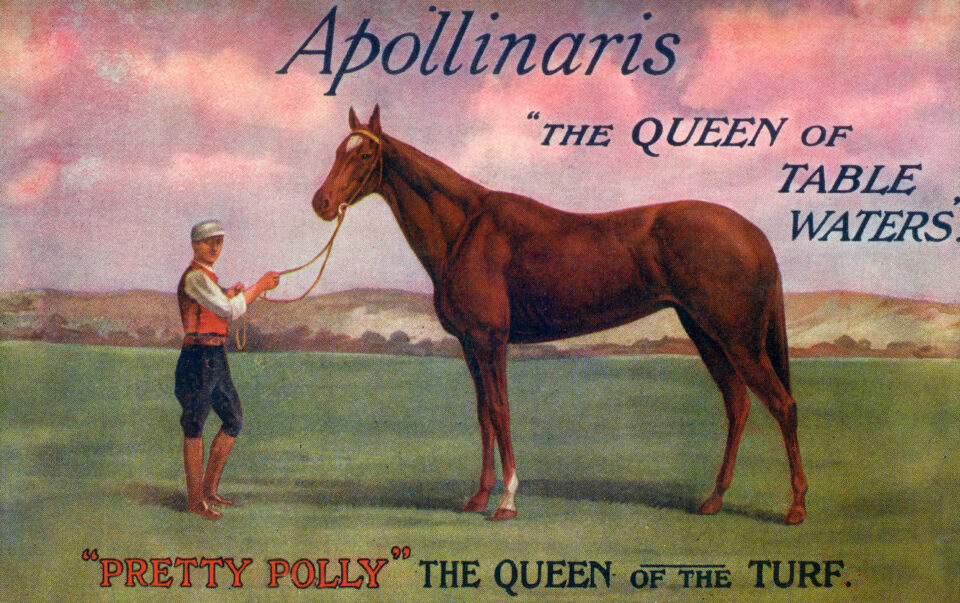

The undoubted equine champion of 1904 was Pretty Polly. In winning the 1,000 Guineas, Oaks and St Leger, she showed that she was every bit as brilliant as Sceptre, if not better. Trained at Newmarket by Peter Gilpin, she was ridden in all three Classics by Willie Lane.

Sadly, Lane’s career was cut short less than two weeks after the St Leger when brought down in a race at Lingfield.

1907

Pretty Polly continued to carry all before her but in 1906 she suffered her first defeat on English soil – her only previous loss was in France two years earlier – when beaten in the Ascot Gold Cup. She arrived at Ascot having won the Coronation Cup and it was assumed she would win easily, but it was not to be. She was headed in the final 100 yards by Bachelor’s Button and beaten a length. That was her last appearance on a racecourse. She was retired to stud having won 22 of her 24 races.

Orby became the first Irish-trained Derby winner in 1907, ridden by American jockey Johnny Reiff. Orby was owned by the Irish-born American Richard ‘Boss’ Croker. Croker was widely believed to have made his fortune through racketeering in New York. When matters became difficult for him in America, he moved to England. Then, when the Jockey Club, aware of his reputation, refused to allow him to have his horses trained in Britain, Croker went instead to Ireland, where he became a leading owner-breeder.

1908

The 1908 Derby was won by the filly Signorinetta, owned, trained and bred by the Italian Chevalier Odorato Ginistrelli. His best horse had been a filly named Signorina and Ginistrelli was determined to breed from her. However, she continually proved barren until showing particular interest in a stallion of little account named Chaleureux. Chaleureux’s apparent mutual affection for Signorina convinced Ginistrelli the two horses must be in love and mated them accordingly. The following year, at the age of 18, Signorina produced Signorinetta. Her form before the Derby was unimpressive and she was sent off a 100-1 outsider but won by two lengths. She followed that by winning the Oaks two days later. The fairy story result immediately turned Ginistrelli into something of an Epsom folk hero.

Danny Maher was crowned champion jockey in 1908, a title he would win again five years later. In contrast to some of the other American riders, Maher was a modest, well-liked man, widely respected for his honesty and skill. Regarded as a supreme stylist, he never let success go to his head. He won the Derby three times during the first decade of the century, on Rock Sand (1903), Cicero (1905) and Spearmint (1906).

1909

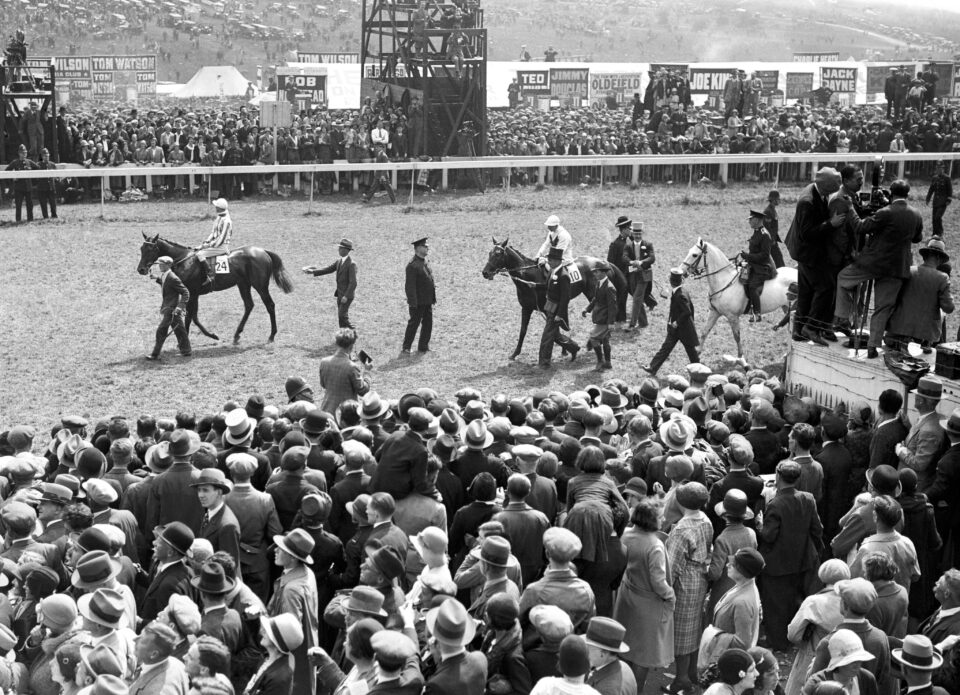

During the course of the decade, several huge betting coups were brought off by the Druid’s Lodge Confederacy, comprising a secretive group of owners based at Druid’s Lodge, near Salisbury. The ‘confederacy’ masterminded the coups, their trainer being little more than a head lad. Among the most spectacular gambles were the victories of Ypsilanti in Kempton’s Jubilee Handicaps in 1903 and 1904; Hackler’s Pride in the same years’ Cambridgeshires; and Christmas Daisy in the Cambridgeshires of 1908 and 1909. The decade ended as it had begun, with a royal Derby winner. When Minoru carried Herbert

Jones, wearing the purple and gold colours of King Edward VII, to victory at Epsom in 1909, it was the first – and so far, only – time a reigning monarch had won the Derby. It was a hugely popular success and, as the crowd surged onto the course, Minoru’s trainer, Richard Marsh, had great difficulty in leading him into the winner’s enclosure.

Minoru was one of six yearlings that had been leased to the King by Colonel William Hall-Walker, a highly respected breeder in Ireland who would later donate his Tully Stud to the nation as the foundation of what would become the National Stud.

Minoru’s Derby victory proved to be the climax of Edward VII’s racing career. He died the following year and the nation went into mourning.

1910

King Edward VII’s death on the evening of 6th May 1910 came as a shock to the nation, as his illness had not been widely known. Of all the tributes which materialised following his death, none was more touching than the spectacle of what has forever after been known as ‘Black Ascot’.

Six weeks after his death, the four-day meeting – it was not generally referred to as ‘Royal Ascot’ until after the Second World War – took place in an air of sombre mourning. On the opening day, The Times carried a solemn reminder from the Home Secretary: “Lord Churchill wishes to remind ladies and gentlemen attending Ascot Races in the Royal Enclosure that they should wear black, as the period of full mourning is not yet expired.”

The race cards were edged in black, the Royal Stand was closed and the blinds of the empty Royal Box were drawn. During the period of court mourning, the royal horses were leased to Lord Derby.

Although the King’s Minoru had won the previous year’s 2,000 Guineas and Derby, it was generally agreed that Bayardo had been the best horse of his generation. He had trounced Minoru in the St Leger and confirmed his status when temporarily lifting the gloom over Black Ascot in winning the 1910 Gold Cup by four lengths.

1913

Bayardo’s half-brother Lemberg won the 1910 Derby, while the 1911 renewal saw Sunstar add the Derby to his 2,000 Guineas triumph. The 1912 Derby was won by Tagalie, the last filly to win the Derby at Epsom.

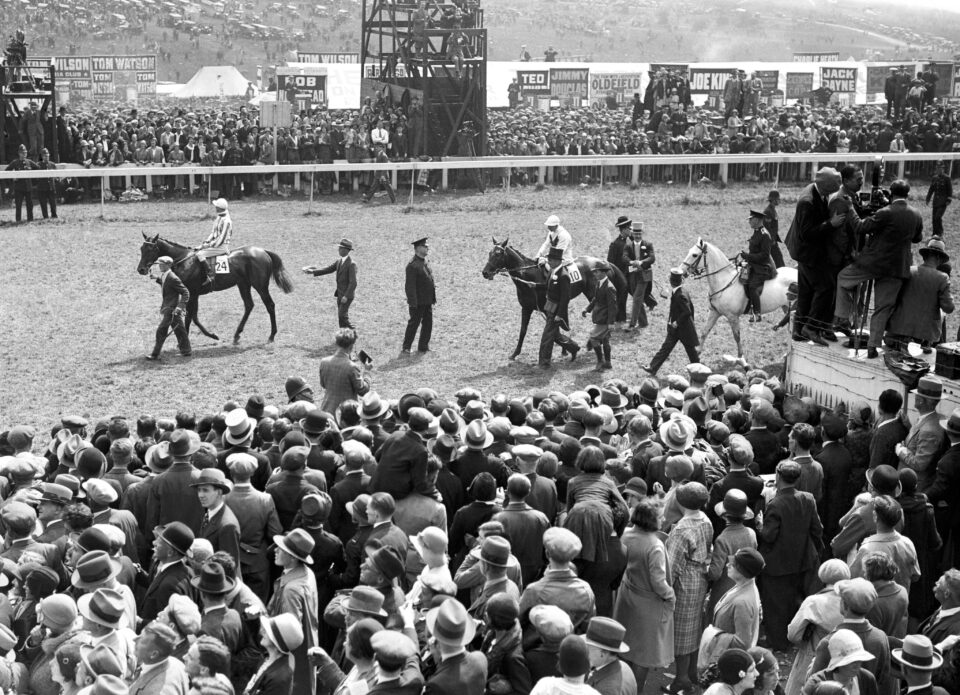

However, none of those three Derby winners’ names is recalled as often as that of Aboyeur, winner of the extraordinary ‘Suffragette Derby’ of 1913. The first sensation occurred at Tattenham Corner, where suffragette Emily Davison ran out onto the course and brought down the King’s horse Anmer. The horse plunged to the ground, hurling jockey Herbert Jones into the Epsom turf, while Davison was flung clear like a rag doll. She suffered a fractured skull, never regained consciousness and died in Epsom Cottage Hospital four days later. Jones escaped with minor injuries.

Meanwhile, the race climaxed in a desperate struggle between the 6-4 favourite Craganour and 100-1 outsider Aboyeur, with the judge awarding the race to Craganour by a head. However, the stewards decided to hold an inquiry, albeit without the usual precursor of an objection, which led to Craganour being controversially disqualified for interference and the race awarded to Aboyeur. One particular two-year-old stood out in 1913. His name was The Tetrarch. He rampaged through the season unbeaten in seven starts. Known as the ‘Spotted Wonder’, he was one of the most remarkable horses in the history of the British Turf.

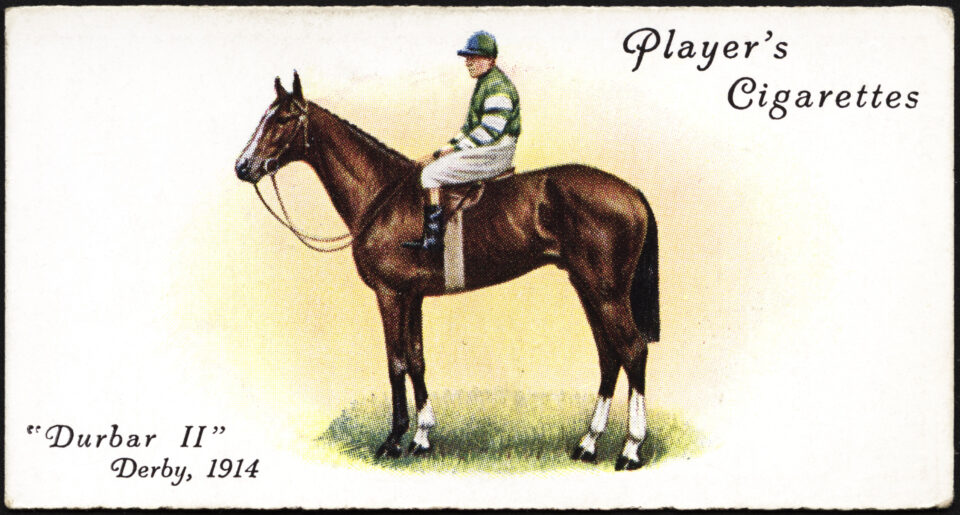

1914

By 1913, the General Stud Book – the official genealogical record of the British Thoroughbred, established in 1791 by James Weatherby – listed 180-American-bred mares in Britain. In an effort to stem the flow of imports from the United States, a Jockey Club committee chaired by Lord Jersey instructed Weatherbys that, from thereon, a horse was only to be considered a thoroughbred if it could be “traced without flaw on both sire’s and dam’s side of its pedigree to horses and mares themselves already accepted in earlier volumes of the book”.

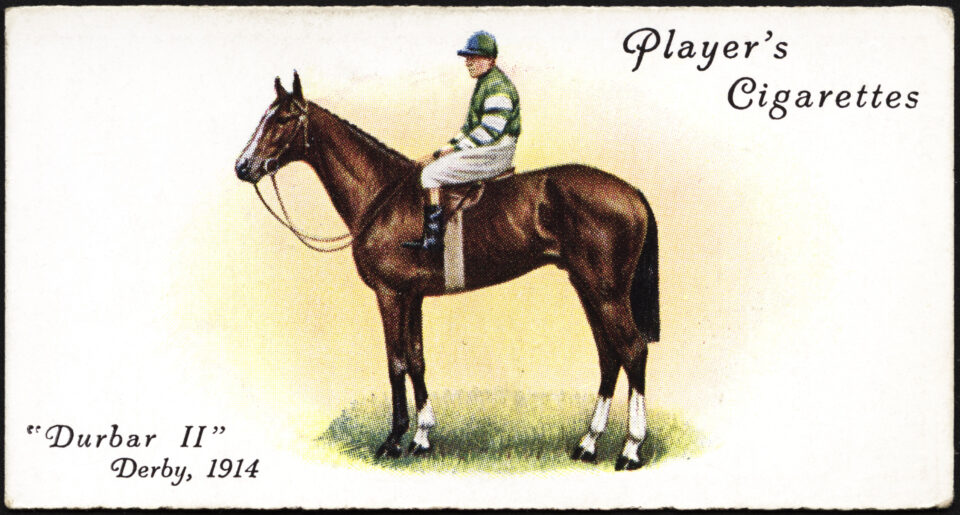

Known as the ‘Jersey Act’, it caused indignation in the United States as it effectively barred many American-bred horses from the General Stud Book as this was a condition that most of them could not fulfil. It thus stigmatised many notable American families as ‘half-bred’. Moreover, it had the effect of cutting off the British thoroughbred from associating with some of the world’s best bloodlines. Ironically, the 1914 Derby was won by Durbar, the first French-trained horse to win it, who was regarded as a ‘half-bred’ under the strict regulations of the Jersey Act. Despite the rule causing considerable ill-feeling throughout the inter-war period, it was not repealed until 1949.

1915

When war was declared in August 1914, horse racing initially continued unaffected. The general feeling was that it would be over by Christmas. However, by the spring of 1915 the reality of World War One had set in.

Pommern, trained by Charles Peck, won that year’s 2,000 Guineas and Derby, the latter taking place at Newmarket instead of Epsom, giving jockey Steve Donoghue his first Derby success. Due to the war, there was no St Leger. Moreover, Doncaster Race Committee refused to allow a race of that title to be run elsewhere, hence Pommern won its replacement, the 1¾-mile September Stakes at Newmarket, to effectively become a Triple Crown winner. Also in 1915, the successful breeder William Hall Walker, a member of a wealthy Lancashire brewing family, startled the racing world by offering to sell his Tully Stud, on the outskirts of the Curragh, along with all its bloodstock, to the British government at a figure considerably less than its true value. The offer was declined at first but subsequently accepted, becoming the foundation for what was to become the National Stud, now based at Newmarket.

The motives for Hall Walker suddenly opting to dispose of something on which he had lavished so much time, effort and expense were never fully explained, although one theory is that it was due to apprehensions concerning the political outlook in Ireland (the 1916 Easter rebellion occurred just a few months later). Whatever the reason, his gift to the nation resulted in him being elevated to the peerage four years later, choosing the title Lord Wavertree.

1917

In 1916, Fifinella, trained by Dick Dawson and the mount of Joe Childs, became the last filly to win the Derby, albeit a war substitute one. Two days later she added the Oaks in a canter by five lengths. Fifinella owed her Derby success largely to the poor quality of that year’s colts. By far the best of them, Hurry On, had not been entered for it. Trained by Fred Darling at Beckhampton, Hurry On had been considered too backward to run at two. He ran only as a three-year-old, winning all six starts without being extended, most notably the September Stakes, the war substitute St Leger. Darling, who numbered seven Derby winners among his 19 Classic victories, rated Hurry On the best he ever trained.

Racing continued on a restricted scale in 1917 and produced a Triple Crown winner in Gay Crusader, trained by Alec Taylor at Manton and ridden by Steve Donoghue. Beaten on his three-year-old debut at Newmarket’s Craven meeting, Gay Crusader then went undefeated in his other seven races that season including the three colts’ classics, the Newmarket Gold Cup (the war substitute Ascot Gold Cup) and the Champion Stakes. Tendon trouble prevented Gay Crusader from running as a four-year-old. Retired to stud, he was only moderately successful. Donoghue rated him the best horse he ever rode.

1918

Alec Taylor trained another Triple Crown winner in 1918. This was Gainsborough, the first Derby winner to be owned by a woman, Lady James Douglas.

Born Martha Lucy Hennessy, a member of the Anglo-French family of cognac distillers, she had married Lord James Douglas in 1888. She bred Gainsborough at her Harwood Stud property near Newbury. Her policy was to sell all her yearlings but she was persuaded by Taylor, who had trained Gainsborough’s sire, Bayardo, to put a 2,000 guineas reserve on the colt when sending him to Newmarket sales. Thanks to Taylor’s insistence, Gainsborough went unsold.

Ridden throughout by Joe Childs, Gainsborough won the 2,000 Guineas, making his owner the first woman owner to win a classic in her own colours. In the Derby, Gainsborough was sent off the odds-on favourite and won by a length and a half from his stablemate Blink. He duly landed the Triple Crown by winning the September Stakes, the wartime substitute St Leger.

Gainsborough went on to become an outstanding success at stud and was twice champion sire. His most notable sons were Derby hero Hyperion and St Leger and Ascot Gold Cup winner Solario, both of whom also became champion sires.

1919

With the war at an end, British racecourses reopened in large numbers. The Derby returned to Epsom where the Irish-bred Grand Parade became only the second black horse to win it, 106 years after the first, Smolensko. Grand Parade was owned by the hugely popular Lord Glanely, a self-made shipping magnate, affectionately known as ‘Old Guts and Gaiters’.

Lord Glanely also owned seven winners at that year’s Ascot meeting which resumed following its four-year absence. Among its highlights was the victory of the four-year-old Irish Elegance, who won the Royal Hunt Cup by a length and a half carrying 9st 11lb, the highest weight ever carried by a winner of the race. Later that year, Irish Elegance carried 10st 2lb to a three-length triumph in Doncaster’s Portland Handicap.

Among the most popular horses of the time was Diadem. She raced for six seasons and won 24 races. They included the 1917 1,000 Guineas but she was better known as a sprinter. At Ascot in 1919 she won the Rous Memorial Stakes then turned out again the next day to win the King’s Stand Stakes.

Diadem was the second of three consecutive wartime 1,000 Guineas winners trained by George Lambton, following the victory of Canyon in 1916 and preceding that of Ferry in 1918. She was commemorated by the Diadem Stakes at Ascot. First run in 1946, it took place in the autumn and was promoted from Group 3 to Group 2 level in 1996. In 2011 it was elevated further to Group 1 status and renamed the British Champions Sprint Stakes, part of the newly created QIPCO British Champions Day.

1920

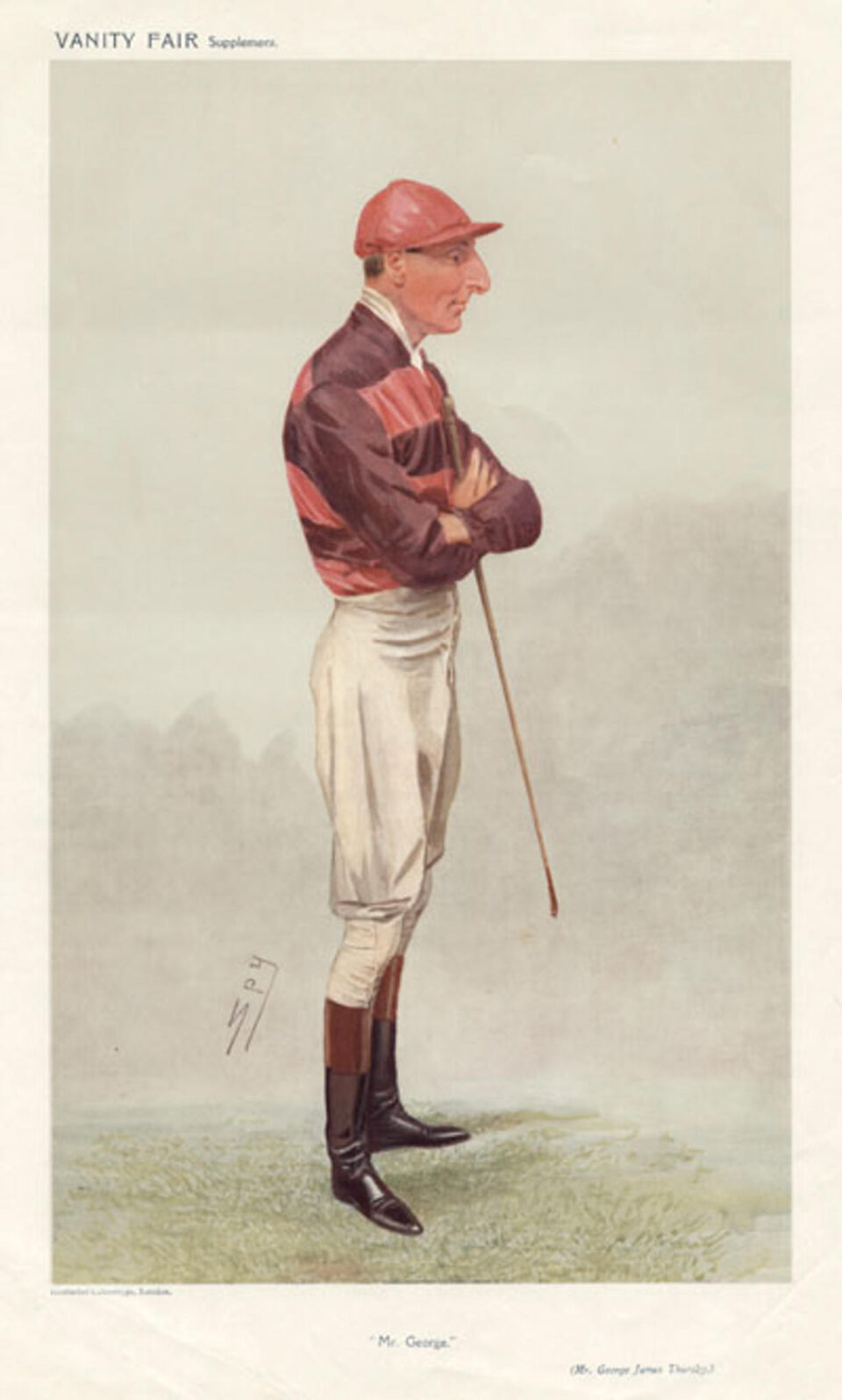

During the 19th century it had been common practice for amateurs to ride on equal terms against professionals on the Flat, as they still do today over jumps. Indeed, some amateurs were as proficient as all but the top professionals. It had pretty much died out by the start of the 20th century, with the notable exception of George Thursby, the only amateur to have been placed in the Derby – he finished second twice, in 1904 and 1906.

Because of his exceptional ability, Thursby had earned special dispensation from the Jockey Club to compete on level terms with professionals. However, in 1920, the Jockey Club imposed a rule banning amateur riders from competing against professionals on the Flat. With Thursby having retired the previous year, the rule had little practical effect.

The Jockey Club brought in another, more relevant, rule change that same year, with owners no longer allowed to use assumed names. This had long been a popular practice, with prominent owners such as Alfred Cox, owner of Gay Crusader, Lemberg and Bayardo, choosing to adopt the nom de course of ‘Mr Fairie’. Prominent female owners used pseudonyms to protect their identity, such as Catherine, Duchess of Montrose, who raced as ‘Mr Manton’, and Lillie Langtry, who went by the name of ‘Mr Jersey’.

1921

Wantage trainer Charles Morton and owner Jack Joel enjoyed a successful 23-year association during the first quarter of the 20th century, winning 11 Classic races. The last of those was Humorist, who won the 1921 Derby in the hands of Steve Donoghue, giving the jockey his first Derby triumph at Epsom, his two previous winners having both been in wartime races at Newmarket.

Humorist battled on tenaciously to beat the hot favourite Craig An Eran by a neck. However, he finished so distressed that Morton kept him at Epsom overnight rather than taking him back to Wantage. Humorist was due to run next in the Hardwicke Stakes at Ascot but broke a blood-vessel during his final canter and was withdrawn.

A few days later, the celebrated artist Sir Alfred Munnings arrived at Wantage and made some preliminary sketches, having been commissioned by Joel to paint the horse. Humorist was put back in his box while Munnings took a break. Minutes later he was found dead, having suffered a severe haemorrhage of the lungs. A post-mortem revealed that it was caused by a long-established tubercular condition. He had won the Derby with just one fully-functioning lung.

1922

Several horses have won the Gold Vase – run as the Queen’s Vase since 1960 – and the Ascot Gold Cup, the most recent example being Stradivarius. But very few have won both races in the same year. The last to achieve this feat was Golden Myth in 1922.

Not only did Golden Myth win those two demanding stamina tests just two days apart, clocking record times in both, he returned to action the following month to win the Eclipse Stakes over the much shorter distance of a mile and a quarter, beating that year’s Derby runner-up Tamar by a head. Golden Myth was the first good horse trained by Jack Jarvis, who later reflected that he was the one that “really put me on the map as a trainer”.

Golden Myth was also instrumental in launching the career of jockey Charlie Elliott, who rode him to all three of those victories. Elliott (spelling discrepancy) had ridden his first winner only the previous year and would twice become champion jockey while still apprenticed to Jarvis.

Also in 1922, number-cloths were carried for the first time on the Flat in Britain. They had been used under National Hunt rules since 1910.

1923

Having won the Derby on Humorist in 1921 and on Captain Cuttle in 1922, Steve Donoghue won it for a third successive year on Papyrus in 1923.

Later that season, Papyrus started a hot favourite for the St Leger but was beaten by Lord Derby’s filly Tranquil. Before the race, Ben Irish, the owner of Papyrus, had accepted an invitation to send his horse to America to take on that year’s Kentucky Derby winner Zev in a match race at New York’s Belmont Park. Sadly, the race proved a non-event. Heavy rain turned the dirt track into a sea of mud and Papyrus’s trainer, Basil Jarvis, refused to heed advice from American trainers to fit him with American ‘mud caulk’ shoes to enable him to get a better grip on the sloppy surface. Consequently, Papyrus was unable to act in the conditions and Zev trounced his English rival by five lengths.

Donoghue had been Britain’s champion jockey for the nine previous years 1914-1922, achieving a career-best score of 143 in 1920. He was champion again in 1923 but this time was forced to share the title with 19-year-old Charlie Elliott with 89 winners apiece.

1924

The family after whom Britain’s most famous Flat race was named ended a 137-year drought when Sansovino won the 1924 Derby for Lord Derby. Having inaugurated the race in 1780, the 12th Earl of Derby had won it with Sir Peter Teazle in 1787. But they had achieved no further success in the race until the 17th Earl finally broke the spell with Sansovino, who was trained at Newmarket by George Lambton.

Incessant rain leading up to the Derby had rendered the ground heavy, conditions which suited Sansovino, a thorough stayer. He was in front coming down the hill, two lengths clear at Tattenham Corner and stayed on in the straight to win by six lengths under his 22-year-old rider Tommy Weston.

An unusual sequel was that, when putting on Lord Derby’s black silks, Weston had inadvertently wrapped part of his white stock (scarf) around one of the buttons. After the race, Lord Derby noticed this and, taking it as sign of good luck, thereafter registered his colours as ‘black jacket with one white button’, a tradition that has been continued by future Lord Derbys to this day.

1926

In 1925 the 2,000 Guineas and Derby were won by Manna, trained by Fred Darling, and the 1,000 Guineas and Oaks by the Alec Taylor-trained Saucy Sue. The St Leger was eagerly awaited as the first meeting between the two dual classic winners, only for Saucy Sue to be scratched, with Taylor convinced that she would not stay the mile-and-three-quarter trip. As things turned out, neither of them would have beaten Solario, who had finished an unlucky fourth to Manna in the Derby and then beaten him easily in the Ascot Derby. By far the best of his generation, Solario trounced the St Leger field in a common canter.

Solario was trained at Newmarket by Reg Day and ridden to classic glory by Joe Childs. As a four-year-old in 1926 he won the Coronation Cup by 15 lengths and the Ascot Gold Cup by three. His name is recalled today by the Group 3 Solario Stakes at Sandown Park.

In addition to his Coronation Cup and Gold Cup wins on Solario, Childs won that year’s Derby and St Leger on Coronach, trained, like Manna, by Fred Darling.

Also in 1926, Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill imposed a 10 per cent turnover tax on all bets made with bookmakers. The tax not only provoked hostility but also proved unworkable. Its lamentable failure forced Churchill to abandon it three years later.

1927

The 2,000 Guineas winner Colorado and Derby winner Coronach stayed in training as four-year-olds in 1927. Both horses had won twice that season before meeting in the Princess of Wales’s Stakes at Newmarket. Coronach had won Epsom’s Coronation Cup and Ascot’s Hardwicke Stakes and was sent off the red-hot favourite at 7-2 on. However, following a brief struggle, Colorado drew right away to win easily by eight lengths. They met again two weeks later in the Eclipse Stakes and it produced a similar result, Colorado beating Coronach by seven lengths.

The 1927 Derby, won by the 4-1 favourite Call Boy, was the first to be broadcast live on radio by the BBC. Call Boy never ran again and was sold for £60,000 as a potential stallion. Unfortunately for his new owner, he proved virtually sterile at stud.

Call Boy was the first of three Derby winners ridden by Charlie Elliott, whose career spanned more than 30 years. A stylish and gifted rider, he was twice champion jockey while still an apprentice and would go on to win 14 British Classics and four editions of the French Derby.

1929

The filly Scuttle provided King George V with what would be his sole classic victory when winning the 1928 1,000 Guineas. She was the first classic winner to be bred and owned by a reigning monarch. Her rider, Joe Childs, declared Scuttle’s victory to be the proudest moment of his life.

With Churchill’s betting tax proving unworkable and shortly to be rescinded, a Private Members’ Bill to create a totalisator system overcame opposition from bookmakers to become law as the Racecourse Betting Act 1928. The Racecourse Betting Control Board was founded to organise and introduce the Tote.

Racecourses began work on constructing totalisator buildings and, following an initial trial at the Old Surrey and Burstow bona fide National Hunt meeting in April, the Tote duly made its racecourse debut at both Carlisle and Newmarket on 2nd July 1929.

The previous month at Ascot, the penultimate race on the final day, the Queen Alexandra Stakes, saw Steve Donoghue gain his only success of the meeting, riding a horse that had won the Champion Hurdle the previous year. His name was not overly familiar then but would soon become so. He was called Brown Jack, the most popular stayer of the inter-war period.

The unpredictable British weather wreaked havoc on the second day of Ascot 1930. A thunderstorm broke out just as The Macnab was being led in after winning the Royal Hunt Cup. The intensity of the storm grew rapidly and torrential rain engulfed the enclosures, resulting in the remainder of the day’s card being abandoned. A bookmaker in Tattersalls was killed when struck by lightning. There were chaotic scenes as male and female racegoers, their clothes soaked and ruined, found their cars bogged down in mud, while those who had travelled by train were confronted by two feet of water in the tunnel to the station.

There had been no such meteorological issues at Epsom two weeks earlier, when Blenheim had given His Highness the Aga Khan his first Derby winner, coming with a strong run in the last furlong to win by a length following a typical waiting ride by Harry Wragg. Freddie Fox was the season’s champion jockey, beating Gordon Richards in a battle that went down to the final day at Manchester. Fox went into it with a lead of one, Richards won the first race and then went into the lead by winning the third, but Fox won the fourth and fifth races to take the title by one.

1931

The 1931 Derby was the first to be shown on television. In fact, it was the first live outside television broadcast of any sport in Britain. Provided by the Baird Television Company in cooperation with the BBC, it used the filming equipment of the former and the transmission facilities of the latter.

The weather was perfect and viewers – albeit the limited number who owned sets – saw a race dominated by the market leaders, with Freddie Fox bringing home 7-2 favourite Cameronian three-parts of a length clear of third favourite Orpen with second favourite Sandwich the same distance away in third.

Cameronian followed up by winning the St James’s Palace Stakes at Ascot and started at 6-5 on for the St Leger, only to trail in last of the ten runners behind Sandwich and Orpen. Cameronian’s trainer, Fred Darling, refuted any suggestions that the colt had been ‘got at’ and the stewards took no action but the public remained unconvinced.

The 1932 St Leger produced another extraordinary outcome, resulting in a virtual monopoly for the Aga Khan. Not only did he win it with Firdaussi, ridden by Fox, but his three other runners, Dastur, the filly Udaipour and Taj Kasra, finished second, fourth and fifth.

1933

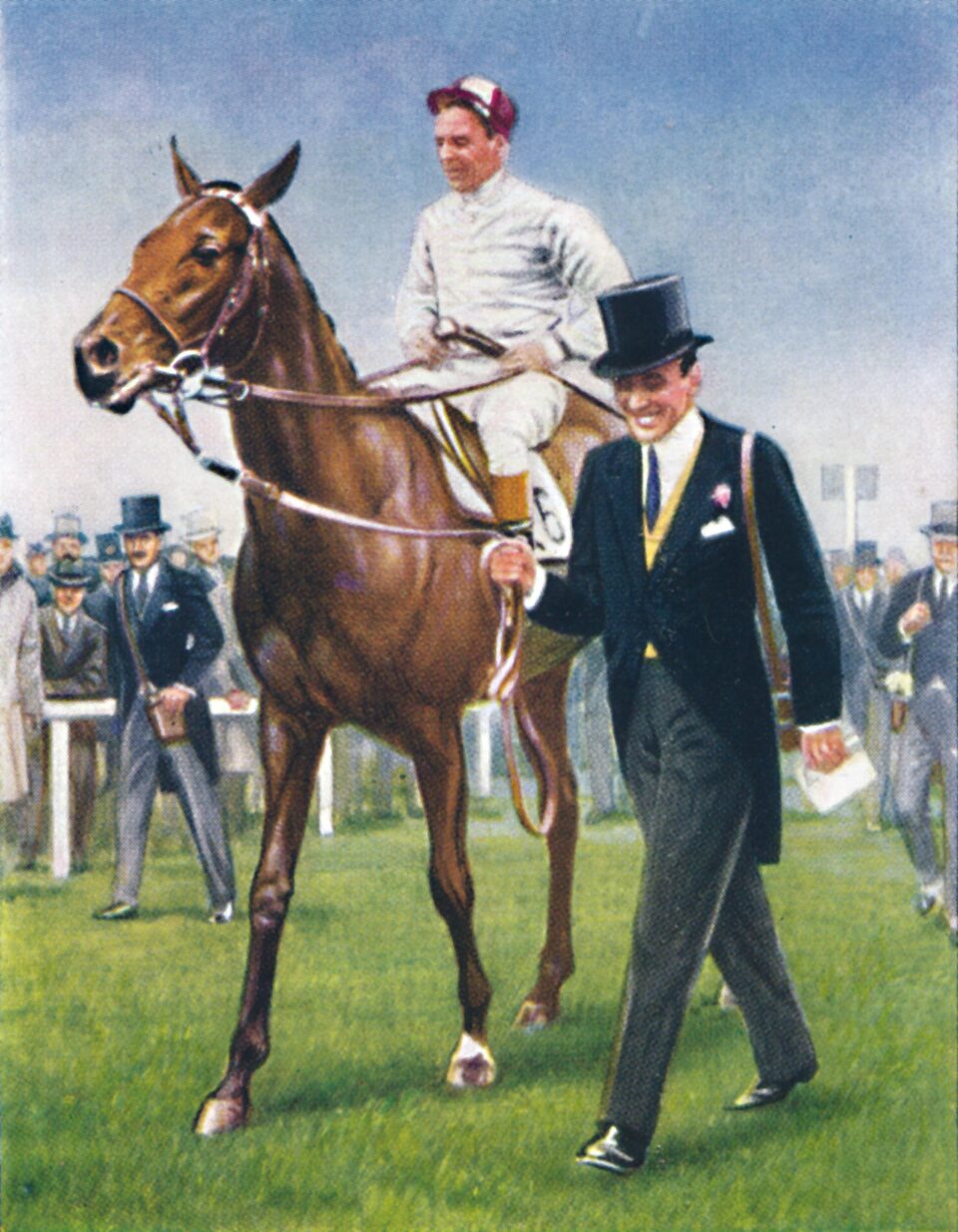

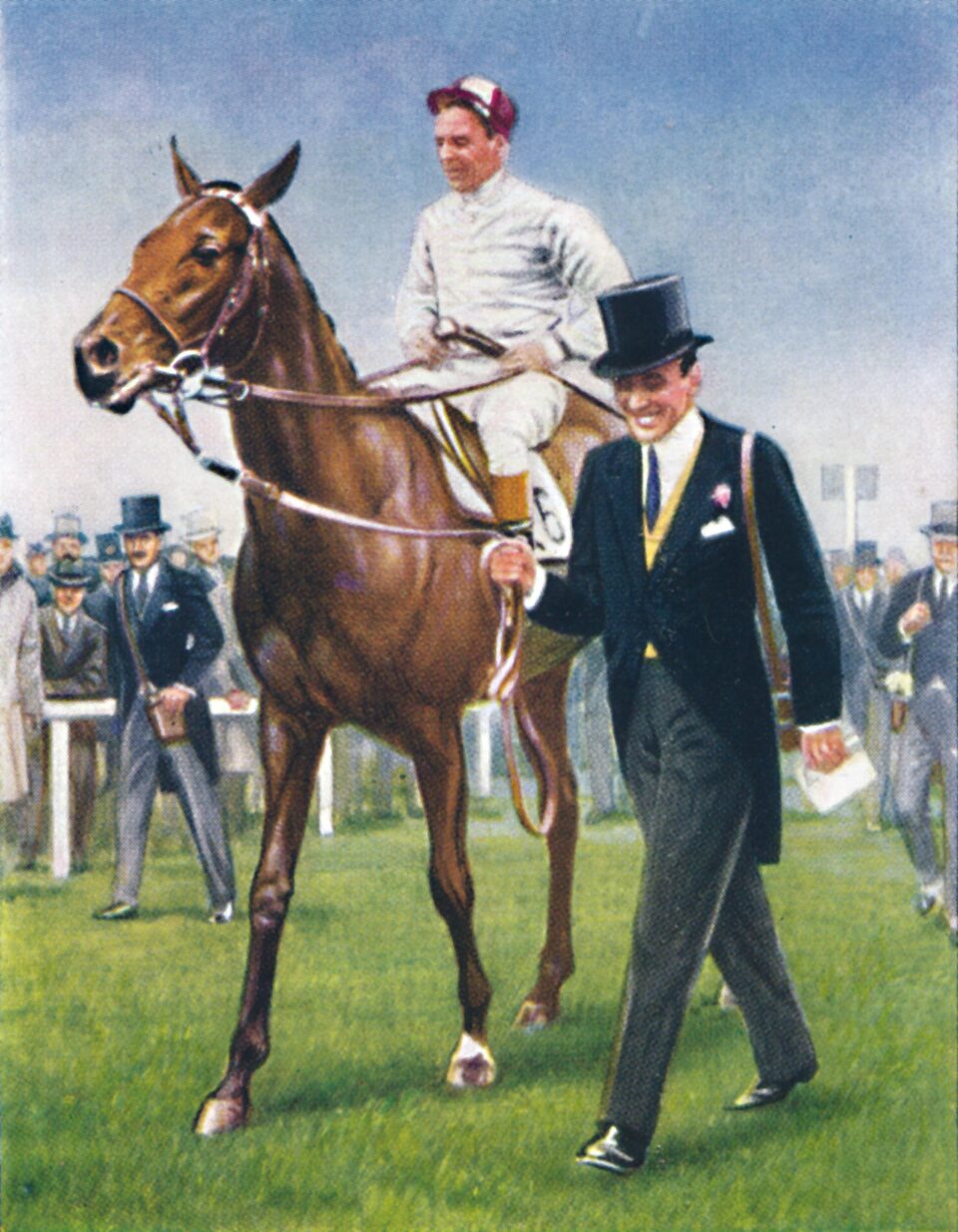

Easily the best horse of 1933 was Lord Derby’s Hyperion, whose victories in the Derby and St Leger were among the outstanding performances of the inter-war years. Standing just over 15 hands, the chestnut with four white socks was reckoned to be the smallest horse to win the Derby since Little Wonder in 1840 and the smallest ever winner of the St Leger.

The jockey of the year was undoubtedly Gordon Richards, who had taken over from Steve Donoghue as Britain’s perennial champion. On 3rd October 1933 Richards won on his last ride of the day at Nottingham. He then won all six at Chepstow the next day and the first five there the day after that. Twelve winners in a row, in itself a remarkable achievement. In addition, it put him within striking distance of Fred Archer’s longstanding record of 246 winners in a season, set in 1885. Since then, only one jockey, Tommy Loates, had ridden 200 winners in a season. Richards had gone close in 1932 with 190. The target was within reach.

With just a few days of the season remaining, Richards rode his 247th winner on Golden King in the Wavertree Selling Plate at Liverpool to break the record. He finished the season with a total of 259 winners. His nearest rival, northern-based Billy Nevett, rode just 73.

1934

Gordon Richards led the way in what was a golden era for jockeys. The only year in which he was not champion during the 1930s was in 1930 itself, when Freddie Fox beat him by one. Fox also won his first Classic that year, the 2,000 Guineas on Diolite. Fox had been consistently successful throughout the 1920s but enjoyed his best seasons during the autumn of his career, winning the Derby twice.

Their contemporaries included the effervescent Charlie Smirke, who also rode two Derby winners during the 1930s; Charlie Elliott, based in France for most of that decade; Tommy Weston, rider of Lord Derby’s two Derby heroes Sansovino and Hyperion, the mercurial Michael Beary, destined to win the Derby on Mid-Day Sun; Harry Wragg, nicknamed ‘The Head Waiter’ for his genius in bringing his mounts with a late burst of speed; Billy Nevett, who dominated the northern scene; Dick Perryman, winner of three 1,000 Guineas and two Ascot Gold Cups; and Australian Bernard ‘Brownie’ Carslake, whose seven British classic winners included the 1934 Oaks on Light Brocade. Meanwhile, Steve Donoghue was still going strong and had one more Classic victory left in him.

1935

The legendary Brown Jack made his farewell appearance under regular pilot Donoghue at Ascot in 1934, winning the Queen Alexandra Stakes for the sixth year running. The ten-yearold’s victory provoked scenes of celebration rarely witnessed on a British racecourse. His retirement was announced immediately after the race.

Brown Jack was all about heart and guts. Not even a Triple Crown winner could rival him in terms of popularity. The year after his retirement, a Triple Crown winner did indeed emerge, one who retired the unbeaten winner of nine races.

The Aga Khan’s colt Bahram was the undisputed star of the 1935 season, winning the 2,000 Guineas, Derby and St Leger. Freddie Fox, who had ridden Bahram in all his races, was forced to miss the St Leger after suffering a fractured skull in a fall at Doncaster the previous day, hence Charlie Smirke deputised and guided Bahram to an easy five-length success.

Although perfectly sound, Bahram was retired to stud forthwith without embarking on a four-year-old career. His detractors insisted that he had never faced a top-class opponent but he could do no more than beat what was put up against him.

1937

The Aga Khan dominated British racing in the mid-1930s. He was leading owner and breeder three times within four years. He followed Bahram’s Triple Crown by owning the first and second in the 1936 Derby, won by the grey Mahmoud from stablemate Taj Akbar.

Firm ground saw Mahmoud set a record time for the race of 2 min 33.4 sec, giving Charlie Smirke his second Derby victory in three years, having won it on Windsor Lad in 1934. Twelve months after Mahmoud’s fastest-ever Derby, there was another notable milestone when Mid-Day Sun, owned by Lettice Miller (officially Mrs G. B. Miller), held off the fast finishing Sandsprite, owned – and unofficially trained – by Mrs Florence Nagle. The result was unexpected, the starting prices of the first two being 100-7 and 100-1, but it struck a chord with both the public and the newspapers. Female owners were still a novelty in those days, while the prospect of women holding trainers’ licences was still decades away.

Mid-Say Sun followed his Epsom triumph by winning the Hardwicke Stakes at Ascot, a meeting which saw the Aga Khan continue to rule the roost with four victories, while his son, Prince Aly Khan, owned Ticca Gari, winner of the King’s Stand Stakes.

1938

Probably the greatest trainer of the inter-war period was Fred Darling. Based at Beckhampton, he won the Derby for the fifth time with Bois Roussel in 1938. He had sent out Pasch to win that year’s 2,000 Guineas and regarded him as his main Derby hope. However, one of his owners, Peter Beatty, returned from France a month before the race with Bois Roussel, whom he had bought after seeing him win a race at Longchamp for horses that had not run before. Bois Roussel showed such promise on the Beckhampton gallops that Darling found it hard to choose between him and Pasch, so staked £1,000 on each for the Derby.

Pasch was sent off the 9-4 favourite while Bois Roussel was a 20-1 chance. Ridden by Charlie Elliott, Bois Roussel produced a strong burst approaching the final furlong to win by four lengths from Scottish Union with Pasch third.

However, easily the best horse of that year was the filly Rockfel. She won the 1,000 Guineas and then made all to win the Oaks in a time considerably faster than Bois Roussel’s in the Derby. In the Champion Stakes later that season she slammed Pasch by five lengths. Her name is recalled today by the Group 2 Rockfel States for two-year-old fillies at Newmarket in October.

1939

On Whitsun bank holiday Monday, 29th May 1939, Lover’s Fate, ridden by future Grand National-winning jockey Dave Dick, won the 16-runner Golden Apple Stakes at Hurst Park. What made the race unusual was that it was the first one open only to horses with female owners. The winner was owned by Mrs H. G. Thurston.

The season was dominated by Lord Rosebery’s colt Blue Peter, trained at Newmarket by Jack Jarvis. Having won the Blue Riband Trial Stakes at Epsom, Blue Peter annexed the 2,000 Guineas and the Derby, then defeated a field which included the previous year’s St Leger winner Scottish Union in the Eclipse Stakes.

There looked to be nothing to stop Blue Peter emulating Bahram in becoming the second Triple Crown hero of the 1930s. However, the declaration of war against Germany, just days before Doncaster’ St Leger meeting, caused all racing to be cancelled with immediate effect due to the fear of air attacks. Racing did not resume until mid-October, having robbed Blue Peter of the Triple Crown he was confidently expected to attain.

Soon after the St Leger had been abandoned, Lord Rosebery took the decision to retire Blue Peter to stud due primarily to the uncertainty surrounding racing’s future during the war.

Soon after war had been declared in September 1939, several racecourses were taken over by the military. The Scots Guards moved into Kempton and the Coldstream Guards into Sandown. Newmarket’s Rowley Mile was requisitioned by the government and would be used by the RAF as an airfield for the duration of the war.

In February 1940 the Stewards of the Jockey Club announced that the 1,000 Guineas and 2,000 Guineas would take place on Newmarket’s July Course. It also decided that with Epsom having already been requisitioned for military purposes, the Derby and the Oaks would both be run at Newbury in June. However, by then troops had taken over the course, hence all that year’s Classics ended up at Newmarket, where the Derby was won by Pont l’Evéque, owned and trained by Fred Darling and ridden by Sam Wragg, and the Oaks by the William Jarvis-trained Godiva, partnered by the apprentice Douglas Marks.

The Derby and Oaks took place on 12th and 13th June respectively. It was only just in time, because the collapse of the French resistance and the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk led to the cancellation of all British racing for the next three months.

1941

Although racing was operating on a very limited scale, there was plenty of opposition to it taking place at all. The Times was particularly condemnatory, while in Parliament, Emmanuel Shinwell MP famously described the continuance of racing as “an insane and unseemly spectacle”. The Jockey Club was thus faced with the delicate job of keeping the sport going, essentially for the sake of the breed, without being seen as impeding or disrupting the war effort.

On 18th February 1941, nine German bombs were dropped on Newmarket High Street, killing 18 people and injuring 61. Birmingham’s racecourse, which had been taken over by the military for use as a gun site and storage of equipment, was heavily bombed by enemy aircraft, with eight bombs landing on the course itself.

A German bomber dropped its load over Newbury’s Flat course in 1941, although ironically far worse damage was to result from the arrival of American troops the following year when the course became a supply depot. Newbury’s turf disappeared under concrete roads while railway lines criss-crossed the course. The stables were turned unto a prisoner of war camp and the Members’ Bar became the officers’ mess. The damage was so severe that it would be four years after the war had ended before Newbury was able to stage racing again.

1942

In March 1942 the Jockey Club announced that racing would be conducted on a regional basis.

Only five courses were permitted to stage meetings. Newmarket-trained horses could only run at Newmarket, northern horses only at Pontefract or Stockton, while those trained south of the River Trent (Newmarket excluded) were restricted to Salisbury and Windsor.

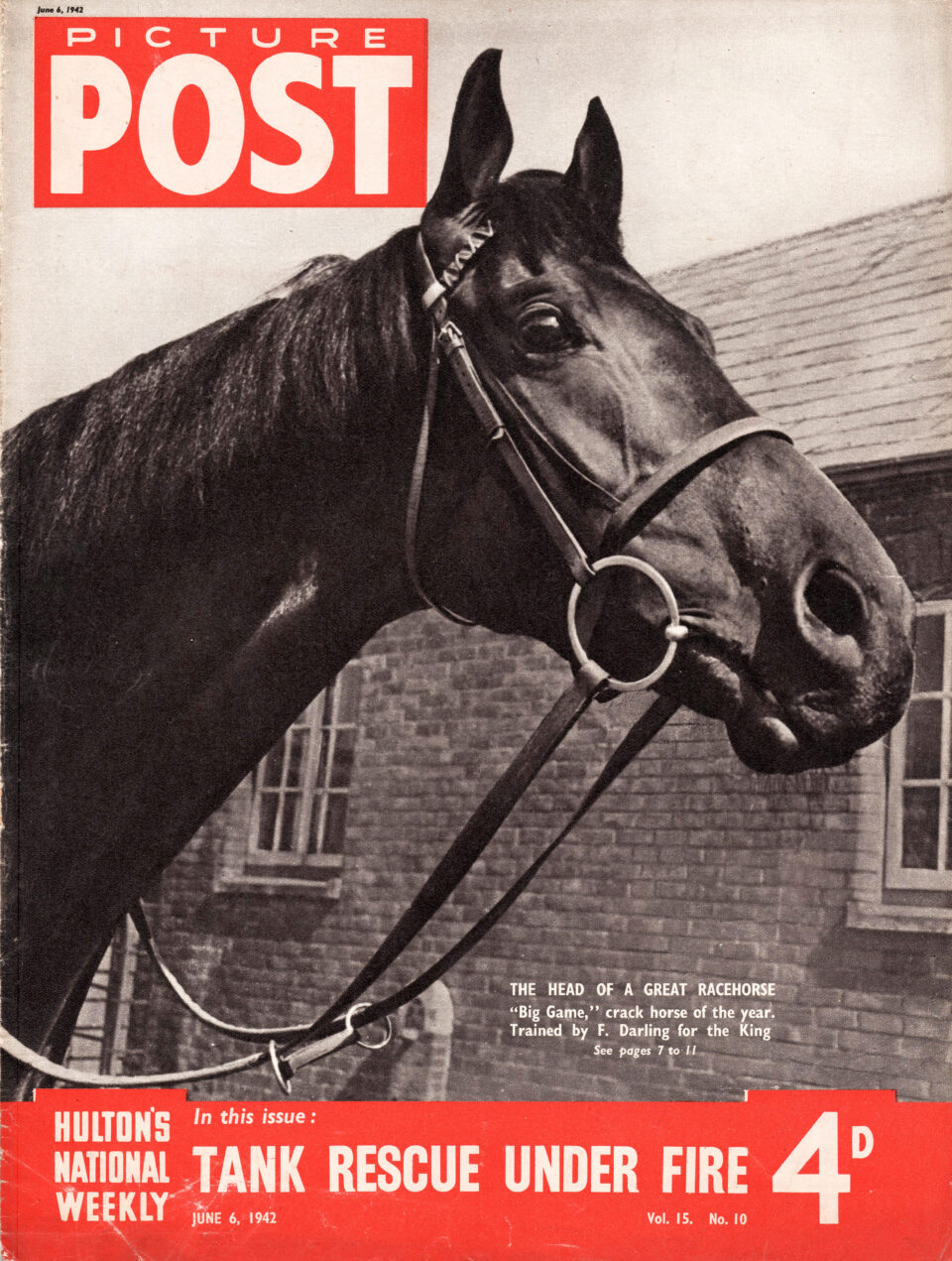

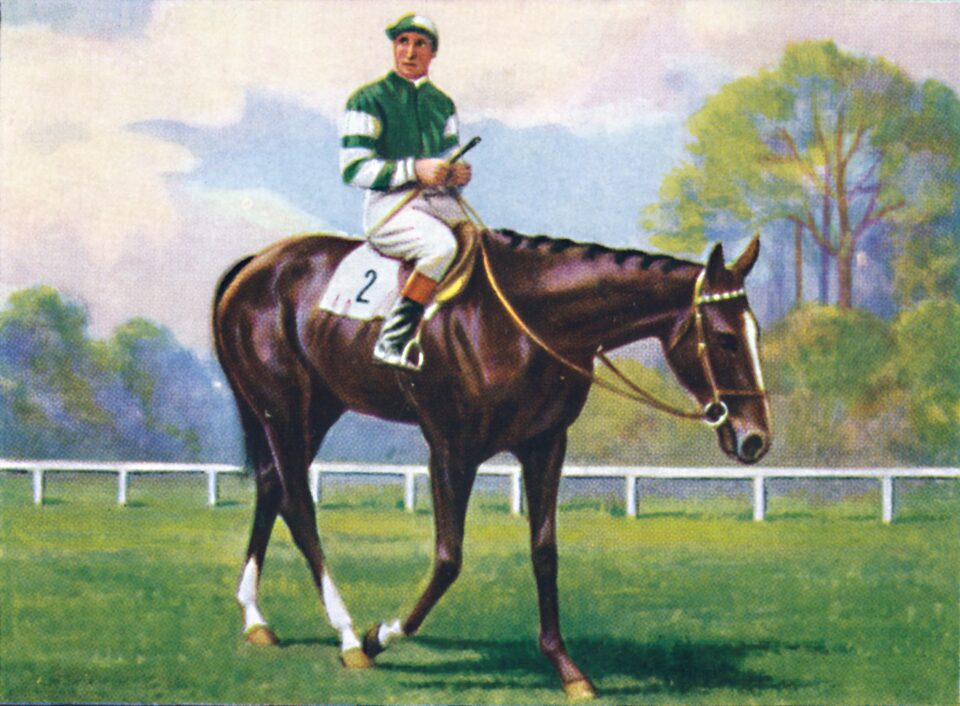

The two best horses of 1942 were both bred by the National Stud, based then in Ireland, and leased to King George VI, who consequently became the year’s leading owner. They were Big Game, winner of the 2,000 Guineas, and Hyperion’s daughter Sun Chariot, who landed the fillies’ Triple Crown of 1,000 Guineas, Oaks and St Leger. Both were ridden to their Classic triumphs by Gordon Richards.

Big Game won the 2,000 Guineas with ease, beating Lord Derby’s colt Watling Street by four lengths. He started odds-on for the Derby and was in front two furlongs from home but failed to stay and finished only fourth behind Watling Street, the mount of Harry Wragg.

The temperamental Sun Chariot was trained, like Big Game, by Fred Darling at Beckhampton. In terms of racing ability, though not longevity, she could arguably be ranked alongside those two great fillies of the early years of the century, Sceptre and Pretty Polly.

1944