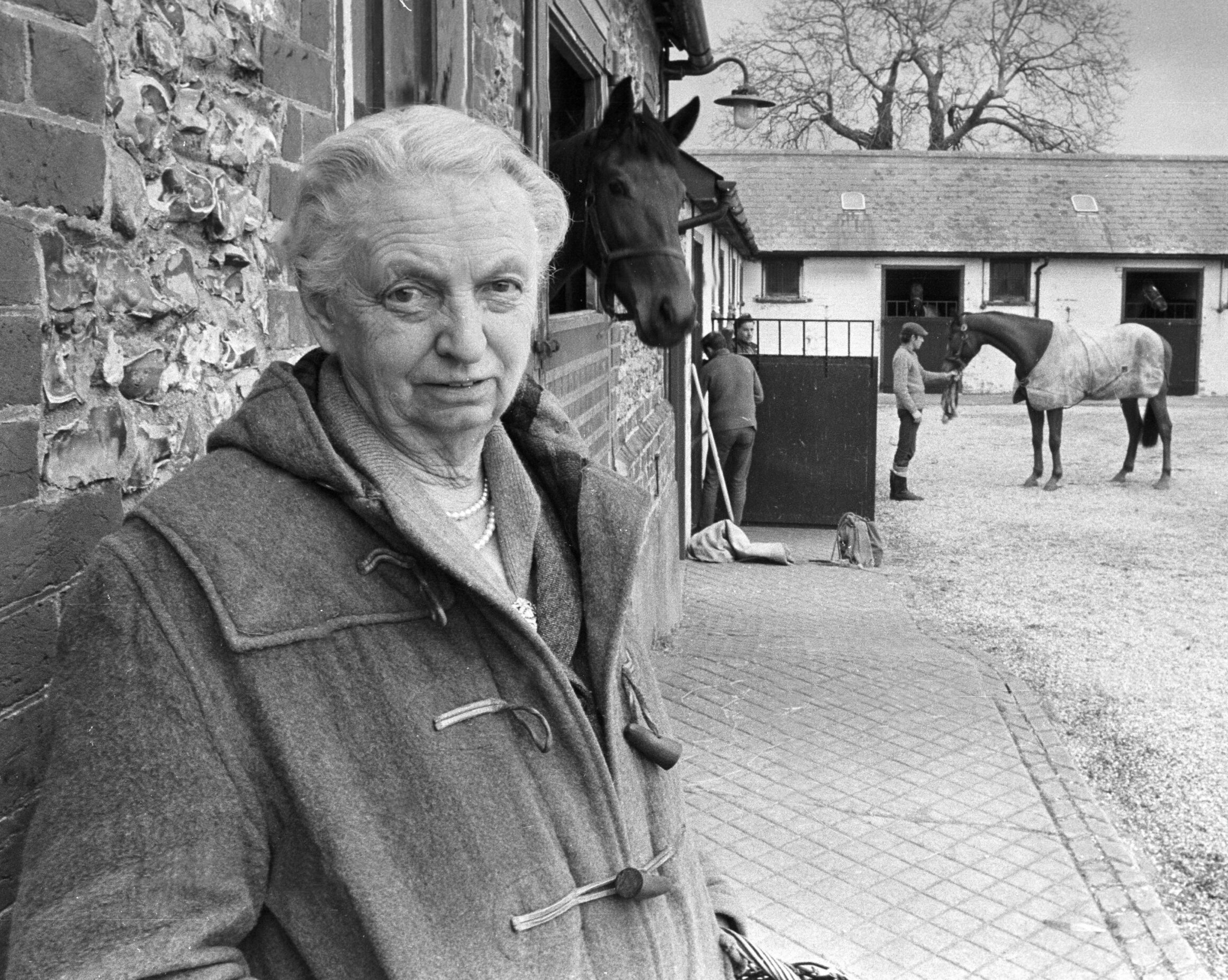

Racing Trailblazers: Florence Nagle

The ‘Trainers’ section in the inaugural edition of ‘Directory of the Turf’, published in 1961, contains a unique entry. It is Florence Nagle’s. Under the heading ‘Date of first trainer’s licence’, she has answered, “Probably never”.

Under ‘Any other details’, she writes: “I should not be in this book as like several other women I am only a ghost, unrecognized, without responsibility, but the fact remains that I train the horses and the mistakes and failures are mine, ditto the rare triumphs. One day perhaps the powers that be will grow up and recognize it is possible for a woman to train a horse.”

Mrs Nagle, then aged 66, trained a string of about 20 at Petworth, in Sussex, but the licence was held by her head man, William Stickley. She had been a racehorse owner since 1920 and a trainer since the early 1930s. Her best horse was Sandsprite, 100-1 runner-up to Mid-day Sun in the 1937 Derby when ridden by the King’s jockey, Jackie Crouch.

Sandsprite was arguably an unlucky loser, having been slowly away and hampered during the race, yet finishing fastest of all to get within a length and a half of the winner.

With Mid-day Sun being owned by a woman, Lettice Miller (officially Mrs G. B.Miller), and the second being owned and trained by a woman, it struck a chord with both the public and the newspapers, receiving extensive front-page coverage in the press.

Mrs Nagle, along with another woman trainer, Norah Wilmot, had been campaigning for more than 20 years for women to be issued with training licences. Their requests were repeatedly refused, effectively forcing them into the subterfuge of having a male employee to hold the licence.

Miss Wilmot, 72, had been training for 30 years, based at Binfield, in Berkshire. The licence was held on her behalf by Robert Greenhill. Her horses included Night Watch, owned by the Queen.

In February 1965 Mrs Nagle had written to the Jockey Club in support of her case. She pointed out that there was no rule forbidding the granting of a trainer’s licence to women; that suitable women had been granted licences in other parts of the world; that Madame du Bois, a leading trainer in Belgium, has entered and run horses in major races at Ascot; and that many male trainers acknowledged that they would be unable to run their stables without girl grooms.

She added that everybody knew and recognised that in certain stables the horses were trained by women and that it was only official recognition that was being denied them.

She concluded: “There has never been a reason given for the refusal to grant licences to women. Surely it would only be fair to state the reason. Last year I was informed by the Acting Steward that I knew the reason. I can only categorically state that I have no idea what the reasons are, as the ones suggested to me by various people were too foolish to be possible.”

When Weatherbys, responding on the Jockey Club’s behalf, again refused her request, she replied: “Your letter, needless to say, does not surprise me. What a passing of the buck from one body to another.

“Naturally, as there is no good reason for the refusal of the Jockey Club, or none that would stand up to publicity, you have to make it confidential, but I shall fight this decision of the ruling body by every means in my power, publicly and privately. Somebody has got to try and drag the Jockey Club into the 20th Century.”

The next step came in January 1966 when Mrs Nagle served a writ against two Jockey Club stewards, Viscount Allendale and Sir Randle Feilden. They were sued individually and on behalf of other stewards and members of the Jockey Club. The writ alleged that Mrs Nagle’s applications for a trainer’s licence had been refused solely on the grounds that she was a woman, and that the stewards’ practice was unlawful, in restraint of trade and contrary to public policy.

The action was initially struck out by Mr Justice John Stephenson, but the following month the Court of Appeal ruled that Mrs Nagle should be allowed to continue her High Court challenge, stating that the Jockey Club stewards’ refusal to grant training licences to women was “arbitrary and entirely out of touch with the present state of society”.

Lord Justice Danckwerts commented on the Jockey Club’s practice of granting a licence to one of Mrs Nagle’s employees: “This seems to me to be simply a childish subterfuge without any merit, and quite unworthy of the importance of the matter.” Facing certain defeat, the Jockey Club capitulated. That summer, Florence Nagle and Norah Wilmot finally won official recognition for women trainers. Mrs Nagle said: “It’s the end of a long fight.”

A momentous piece of British racing history was thus made when, on Thursday, 28 July 1966, Mrs Florence Nagle and Miss Norah Wilmot became the first women to be granted a trainer’s licence. The very next week, on Wednesday, 3 August, Wilmot became the first licensed woman trainer to saddle a winner in Britain when Pat, owned by her friend Miss Pat Wolf, won the South Coast Stakes at Brighton.

By the end of that month, Mrs Nagle and Miss Wilmot had been joined in the training ranks by Louie Dingwall, Gladys Lewis and Auriol Sinclair.

Those pioneers were soon joined by Rosemary Lomax, who became the first woman to train a winner at a Yorkshire track when Welsh Lord won at Catterick on 16 August 1967. Three years later she trained Precipice Wood to win the Gold Cup at Royal Ascot, ridden by Jimmy Lindley.

It seems archaic now, but it should be remembered that the Jockey Club was a self-elected body who at that time enjoyed a monopolistic control over racing, with complete power over everyone who chose to earn a living on the racecourse. They considered themselves as having unfettered discretion and could exercise it without any regard to merits, and without intervention by the courts.

It must have been something of a shock for them to be proven wrong. As Mrs Nagle’s Q.C. had declared during the High Court hearing: “We say that in a case of this kind, the stewards are not above the law.” He was right. They were not above the law. Mrs Nagle had proven that.